Here’s a paradox: Michigan is known around the country for having the one of the longest prison sentences in the country, but even so, more than seven out of every 10 people committed to prison in 2017 were sent to serve short sentences of fewer than three years. How can this be, and what does it mean when so many people are in prison for such short stays?

Report after report shows that Michigan has the longest or among the longest prison sentences of any state in the country. The most recent Michigan Department of Corrections statistical report shows this continues to be the case.

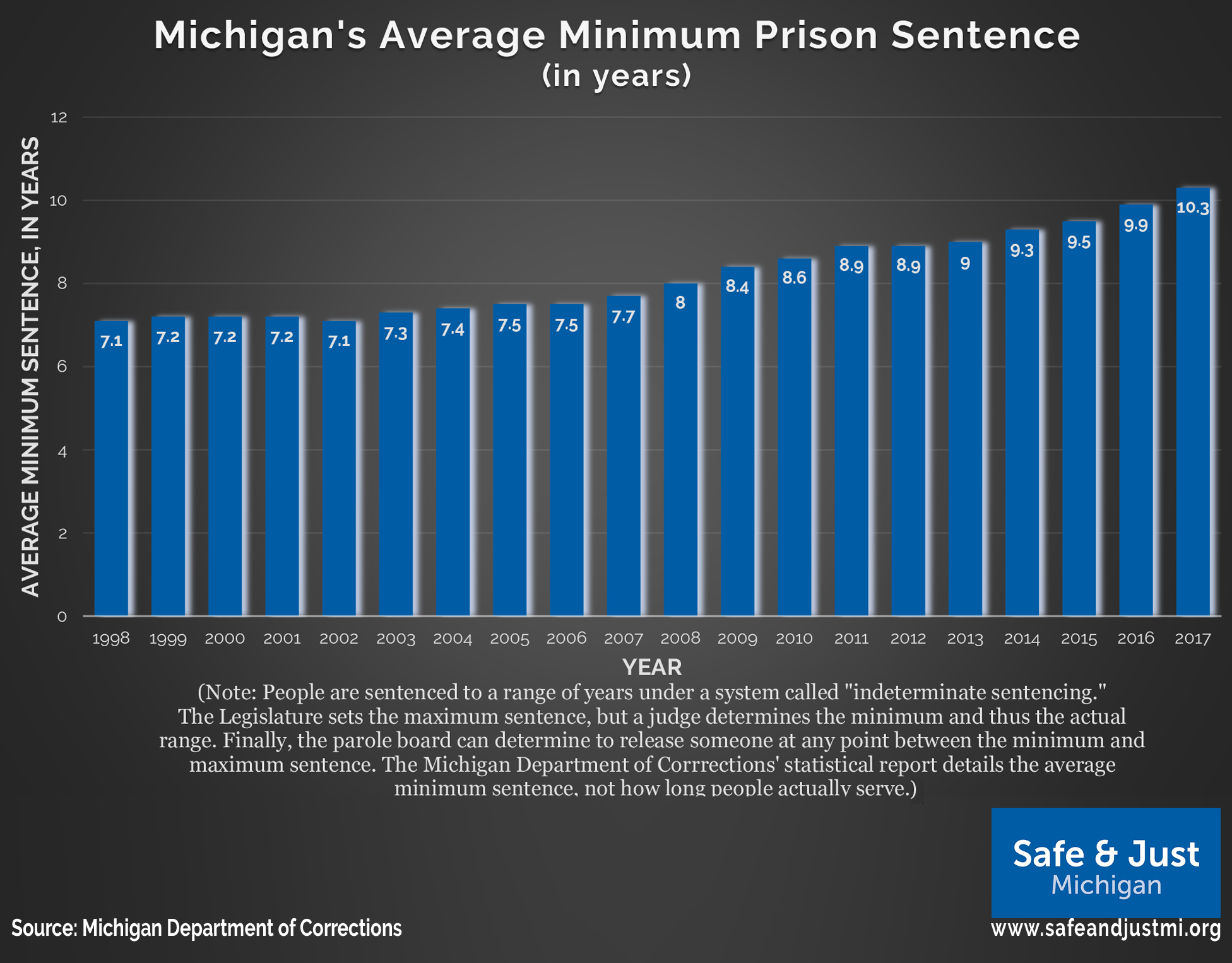

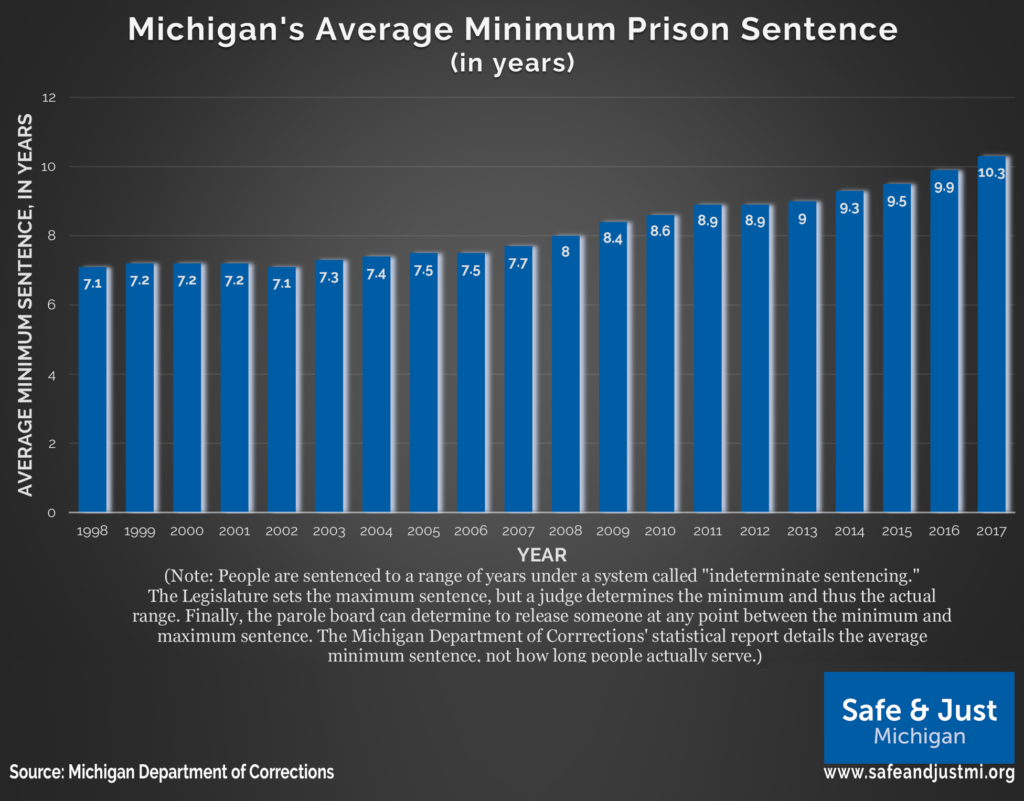

In fact, Michigan’s average prison sentence is actually getting longer even as our overall prison population is shrinking. In its most recent statistical report, using figures from 2017, the MDOC said that average minimum sentence for all kinds of criminal convictions — both violent and nonviolent — was 10.3 years. That’s up 37.3 percent from the average sentence of 7.5 years recorded in 2006, when Michigan’s prison population reached its highest point.

But at the same time, our prisons churn with people serving short sentences for offenses such as the felony firearm and resisting a police officer, which carry a maximum sentence of fewer than three years. As a result, 8,543 people — or 21.5 percent of the total population in prison in 2017 — were there on stays of less than three years.

Michigan’s criminal code is replete with crimes whose guidelines call for a maximum prison stay of less than three years. They include infractions such as possession of a controlled substance, writing a check without having a checking account, breaking into a coin-operated device or the unlawful use of a motor vehicle.

Those are the sentencing maximums set by the Legislature. Judges, however, often set prison stays less than those possible maxims, representing the amount of time someone must serve before they become eligible for parole. For instance, carrying a concealed weapon is a five-year felony according to statue, but in reality, the 221 people incarcerated in Michigan prisons in 2017 under this law were serving an average sentence of 2.2 years. The third offense of operating a vehicle under the influence could bring a prison stay of up to five years, but the average stay of the 727 people incarcerated under this law was 2.1 years. Failure to pay child support could result in a four-year prison sentence, but the average prison stay for the 30 people incarcerated on this offense is 1.9 years — during which time the parent is unable to earn money to support their child.

But just because those sentences are short does not mean they are not costly. At an average expense of $36,106 per person annually, it is costing taxpayers $308.5 million each year to shelter, feed and care for people who have been sentenced to fewer than three years in prison.

People from prosecutors to politicians are fond of saying that prison is the place for the “worst of the worst” among us. But let’s think for a moment about what that really means. Are we truly safer for having bad check writers and vending machine vandals and parents behind on their child support in prison? Are we $308.5 million a year safer? How many of these people and their communities might be better served by community-based alternatives that allow them to keep their jobs, or stay in school, or continue to care for and support their children and families?

“Short prison stays are of questionable utility from a public safety standpoint,” said Safe & Just Michigan Executive Director John Cooper. “They generally arise from low-level misconduct and offer limited opportunities for rehabilitative programming, and they have serious potential downsides: they take a person out of the workforce and out of the home and put them into a hostile environment filled with people that have committed more serious crimes, which can easily lead to more involvement in criminal activity, not less. In light of this, community-based alternatives are often a better investment in public safety than a short prison sentence.”

Further, people who are sent to prison for even minimal stays come home to find their lives immensely changed. They return with little savings and a significant gap in employment they will need to explain to a new employer. And they will likely find it difficult to find a good job, as many employers are reluctant to hire someone that has been to prison. Similarly, many landlords refuse to rent to someone who was formerly incarcerated. Some universities even hesitate to enroll students who have been to prison, or hesitate to admit them into certain academic programs if they believe the student’s criminal record will prevent them from obtaining employment in that field of study.

Safe & Just Michigan, along with our partners, is working to pass Clean Slate legislation this year that will bring more second chances to people in Michigan who have a criminal record. We invite you to learn more about this legislation and to participate in activities we will be holding around the state where you can share your stories about the need for greater expungement opportunities.

In an upcoming blog post, we’ll take a look at Michigan’s long prison sentences, and what they mean for the people serving them, their families and the rest of our state.