Michigan doesn’t have the death penalty, but that doesn’t mean people don’t die in our state’s prisons. In 2017 alone, 106 people died while they were incarcerated in Michigan, according to the Michigan Department of Corrections’ Statistical Report. Many of them were receiving treatment for medical conditions. Things like cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and the advanced stages of kidney disease are more commonly associated hospital beds and nurses than with than prison and corrections officers, but increasingly, the distinction between the two has become blurred.

Michigan’s prisons have had to adapt to deliver an increasing amount of medical and even end-of-life hospice care as our state’s incarcerated population has steadily grown older. And this has placed growing cost pressures on our state’s corrections budget — one of the reasons the cost of maintaining our corrections system has remained fairly constant at about $2 billion annually even as our overall prison population has fallen 23 percent between 2006 and 2017.

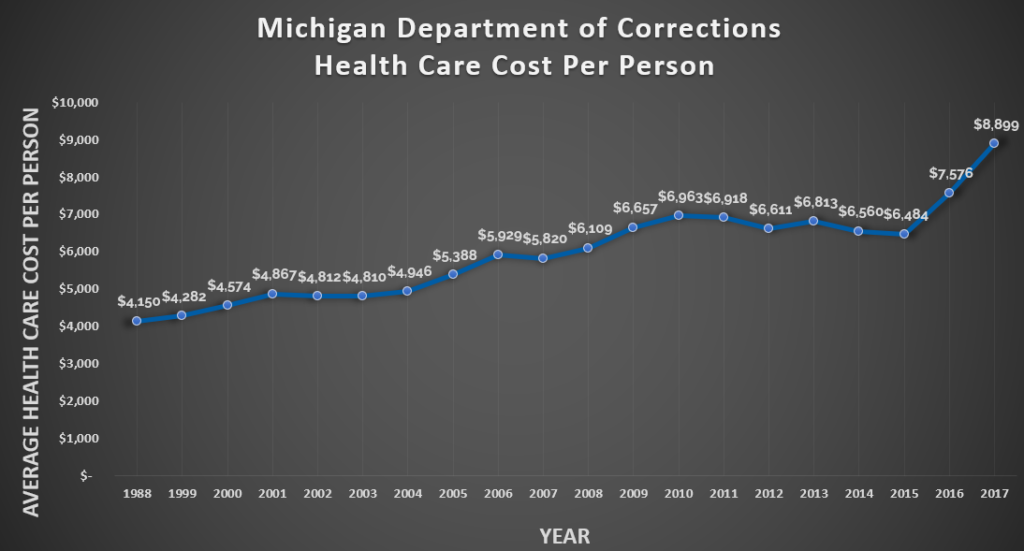

In fact, the average health care cost per person has been on a steady upward march for the past decade. In 2008, the state averaged $6,109 in health care costs per incarcerated person. By 2017, that cost had increased 45.7 percent to $8,899 per person. Those costs include medical, dental, psychological and mental health services.

To make matters worse, prisons are not set up to be effective health care centers. In testimony to the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Corrections on Oct. 18, 2017, MDOC Legislative Liaison Kyle Kaminski said that — with rare exceptions — the state of Michigan bears 100 percent of the cost of medical care for prisoners health care, even though getting that care in a prison setting costs anywhere from 3- to 5-times as much as it would if a patient got it at a regular medical setting.

It’s not hard to see what is driving that cost increase. Rising in tandem with health care costs is the average age of Michigan’s incarcerated population. Back in 1998, the average age of an incarcerated person in Michigan was 34; now, it is 39. Just about a quarter of Michigan’s prison population — 23.2 percent — is over the age of 50. And that number is likely to climb higher as the proportion of people serving life sentences in Michigan increases relative to the number of people serving relatively shorter sentences.

The root of the problem is in Michigan law: in Michigan, all prisoners must serve 100 percent of their minimum sentence in prison — regardless of their physical or mental state — and requires MDOC to cover 100 percent of the costs of their medical care. The MDOC has no authority to parole a prisoner based on their mental or physical frailty, even if a person is too incapacitated by Alzheimer’s disease to know how to feed themselves or too weakened by cancer to move from a bed to a chair. Under current law, a medically frail incarcerated person can either seek a commutation from the governor, but those are rarely granted. Failing that, they will live out their lives in prison.

It’s a problem that the Michigan Department of Corrections is very familiar with, and it’s why it supports legislation to create a medically frail parole law. That provision would allow incarcerated people who are no longer able to complete regular daily tasks such as feeding or dressing themselves to become eligible for parole and be released to a hospital, hospice, nursing home or other housing accommodation providing medical treatment. To be clear, these are people who are so sick that they do not pose a threat to community safety.

While that’s a step in the right direction, this proposal alone won’t solve the problem. For one, the way the proposal is drafted, it will only apply to a very narrow set of people. It has been carefully written to not apply to anyone convicted of first-degree murder or criminal sexual conduct. As a result, if the bills were to pass today, they would apply to fewer than 40 people even though there are currently about 800 people incarcerated in Michigan prisons who are considered medically frail — that’s just 5 percent of all medically frail people.

Safe & Just Michigan and many other organizations, such as the ACLU of Michigan and the American Friends Service Committee’s Michigan Criminal Justice Program, would prefer to see a stronger proposal passed. But there are political headwinds we are fighting against. Some prosecutors don’t want to see this plan applied to people serving life sentences without parole or people convicted of criminal sexual conduct charges, and many lawmakers take their concerns to heart when deciding how to vote.

Still, we believe that a partial solution is better than no solution, and that we can work to improve this plan moving forward. That is why we are supporting this medically frail proposal. The Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan has also come out as neutral on the proposal, which we hope will clear the way for the plan’s passage. On March 12, the plan was voted out of the House Judiciary Committee and on the same day, the full body of the House approved the plan and moved it to the Senate.

While this is a hopeful sign, it is not the only solution we need. Compassionate release alone will not solve the problem of an aging prison population. The underlying problem is a continued reliance on over-incarceration and a growing proportion of the prison population serving long or life sentences.

When we address those fundamental problems, we will start to see the average age of Michigan’s incarcerated population decrease. Only then can the Michigan Department of Corrections start to ease back from its role as a health care provider to the elderly and extremely ill, and only then will Michigan residents start to realize a savings from sound safety policies that are smart on crime and soft on taxpayers.