(Please note: the following blog post contains the reflections of formerly incarcerated people in their own words, and it covers material that is emotionally sensitive such as rape and gun violence.)

Daniel Jones’ life changed forever when his parents separated when he was just a young boy. Up to then, he felt secure and loved. After that, everything changed.

“My parent’s separation left me with a lot of confusion. It left me with a lot of anger. It left me with a lot of fear,” said Jones. “It led to me making a lot of very bad decisions. I knew that intrinsically I wasn’t a bad person, I just didn’t have the know-how to articulate my fear and my anger, and it came out in a way that it caused me to take a person’s life. That’s what I went to prison for.”

When he was just 16-years-old, a judge decided that Jones would never be fit to live among society and sentenced him to prison for the rest of his life. But Jones got a second chance at freedom in 2012, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional, with rare exception, to send juveniles to prison for the rest of their lives without even a possibility of parole. Jones got that chance when he was resentenced, and he was released from prison last year. He now works with the American Friends Service Committee Michigan Criminal Justice Program.

Jones and two other men who were sentenced to prison for long sentences or life spoke about how their childhood experiences led to their incarceration at an event titled “Disrupting the Trauma to Prison Pipeline” at the Robin Theater in Lansing recently. The audience — including many community members who appeared interested in criminal justice reform but who didn’t know how to get invoved — were eager to learn more about their stories and how to make change happen.

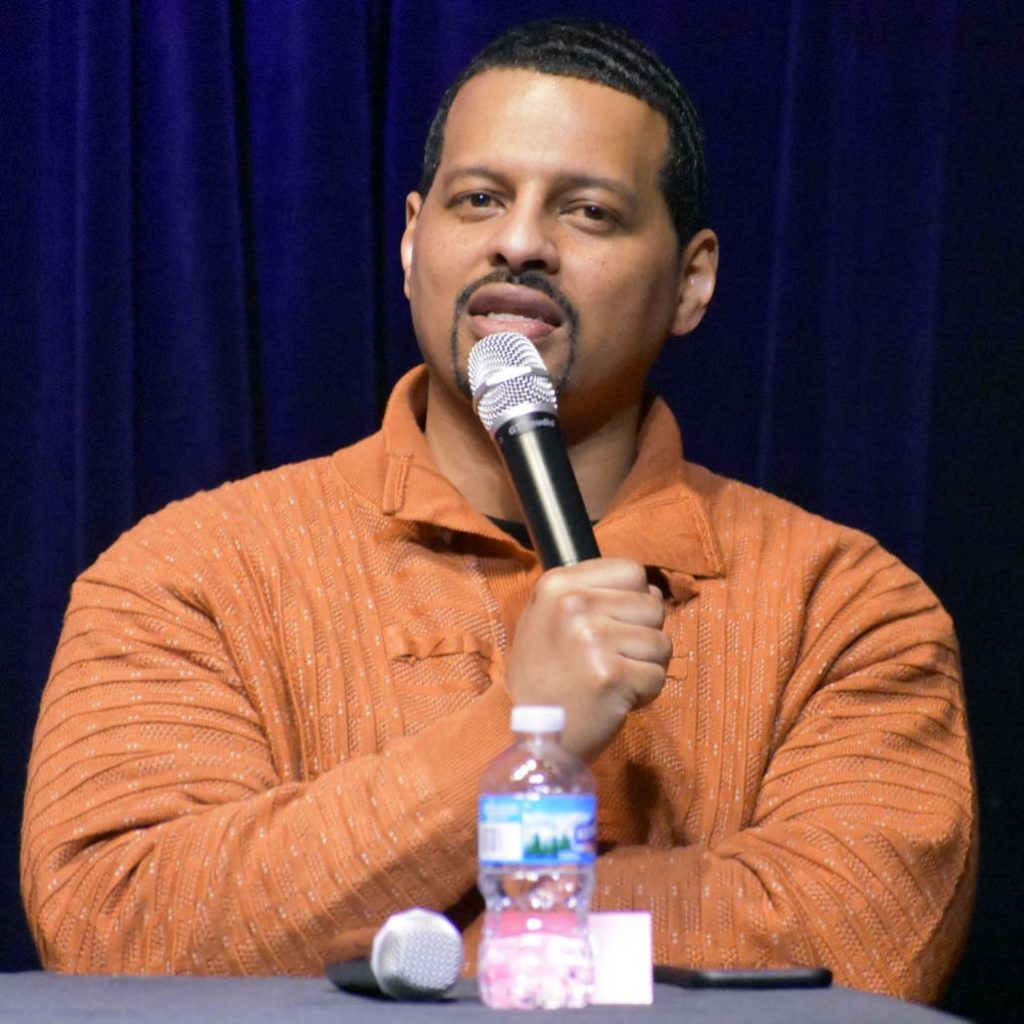

Aaron Kinzel told them that his childhood didn’t resemble a picture book, either. “My earliest memory was around the age of 5 or 6, when I watched the trauma my mother endured,” he said. “She would be beaten or raped by different men who were in her life.”

Aaron Kinzel

In fact, brutality was a daily fact of life in Kinzel’s childhood. “My conception was through a rape,” he explained. As an adult, he can look back and understand things that were beyond his comprehension then. “As a child, all we want to do is have that loving connection with our mother. But my mother had this animosity toward me because I’m sure that just even seeing my face and seeing my father’s eyes was a traumatic experience for her.”

At the time, all he could do was cope. “My stepdad was extremely abusive and would rape (my mother). I watched him turn into the Incredible Hulk. He would just smash the house up in these rages. … I would cry and beg him to not hurt my mama. He would put a gun to her head and say ‘I’m going to kill her if you don’t shut the hell up.’ There was a time he chased me from the home with that gun and fired six rounds from a .357 magnum at me as a little boy. I think that was probably my most traumatic experience as a child.”

Kinzel grew up thinking he had to be just as tough just to survive. By the time he was 18, he had a gun of his own, and he ended up in a shootout with police. That resulted in him being incarcerated out-of-state for a sentence of 19 years, and being paroled after 10. He’s now a professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, where he lectures on criminal justice studies.

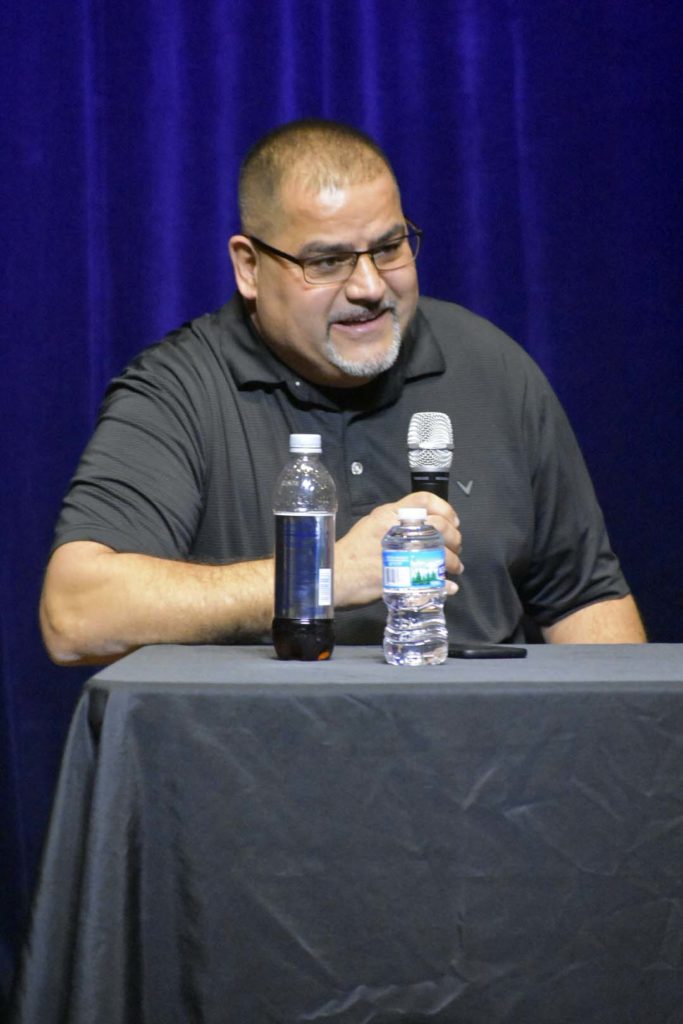

The childhood home of Frank Rodriguez was also violent and unpredictable. “I was 5 or 6 and my parents used to fight, and I remember my dad shooting at my mom in the kitchen,” he said. “I remember my mom dating guys and they thought they could whup me, and I don’t like whupping, so I gave them back. My whole life was like that,” he said.

The streets seemed a safer alternative, and he began selling dope there. That made him popular, he said, but it also got him arrested. Eventually — after fighting the charges while incarcerated in jail for more than four years — it also got him in prison for a sentence that was supposed to last the rest of his life. It took a campaign of people who believed in him, including his prison warden, to earn his release, and he now works for the State Appellate Defender’s Office.

Each of the three men pointed to a turning point that happened during their incarceration that led them to turn their lives around.

For Jones, it was finding mentors in prison who showed him that his future didn’t have to resemble his past.

“I had a few mentors take an interest in my well-being who wanted to see better for me even when I didn’t want to see better for myself,” Jones said. “It took years for me to get to the point where … I was tired of living in prison. I had to face the reality that I created these conditions for myself. I said I’m going to create a different set of conditions for myself. When I joined the NLA (National Lifers Association), that was the first time I heard about improving upon the plight of others. They weren’t even concerned with themselves. They were looking at how they could hep the rest of the prison population. I never heard anyone talk about doing anything like that. When I heard that, it spoke to me.”

Kinzel said it came down to changing the way he viewed himself. He had been wrapped up in convincing others — and himself — that he was a tough guy. Things changed when he started to let go of that:

I started to listen to the lifers. A lot of them had been sent there when they were 15 or 16 but they had changed, they evolved over decades. They were some of the most intelligent men I ever knew in my life. They could recite case law. I realized I could do something with programming (in prison). They taught me to de-escalate violence. These were men who had committed murder who told me you should never commit violence and the only exception to that is if someone is trying to harm you or someone you love. That was not something I was used to. That was weird to hear that from people who had done violent things. That was not what I was used to. I was done with the façade.

Rodriguez agreed that many people in prison buck the stereotype that all incarcerated people are frightening and dangerous.

Frank Rodriguez

“You wouldn’t believe the guys in prison. Not everybody’s bad,” he said. “I spent four years in the county jail and I couldn’t read or write. When I got to prison, this guy said you better learn, so he taught me how to use a typewriter and then I learned case law. Most of you guys learned to read and write with Jack and Jill went up the hill — I learned with case law.”

And becoming literate changed everything in Rodriguez’ life.

“Because I kept reading law, I got a job in the law library. People looked up to me not because I was selling drugs. They look up to me because I know something. I started getting self-esteem,” he said. “For me, that was my turning point, when I could start to read and write. It started opening doors.”

But not all the doors opened willingly, he found. For every prison guard who was willing to help him, there seemed to be another who wanted to stand in the way.

“If you had (a) life (sentence), you couldn’t get programing (such as a GED program), because you’re doing too much time,” he said. “I remember when I was writing, there was a guard who would correct my papers and show me what I was doing wrong. One time he came to my cell and said other officers are going to tell on me, I have to stop. I used to have people steal books out of the GED classrooms so I could look at the books and study because they wouldn’t give me a book.”

All three of the men remarked that mentors made the difference in their lives. Unfortunately, they never found those mentors until they were incarcerated.

“What I needed was consistency,” Jones said, reflecting on his childhood. “I needed somebody to grab me by the hand and walk me through life and say these were the steps that needed to be taken. … We need programs with mentors who are there constantly. People have to be able to see you consistently to know that this is how you live your life.”

It is also important for people who have not been involved with the justice system to get to know people who have been, Jones said. There are a lot of myths and misunderstandings about how the justice systems work, and how prisons do — or do not — make or communities safer. Getting to know people who have been incarcerated will help people understand the changes that need to be made, and they can help people who have been incarcerated feel heard and understood as well.

Daniel Jones

“I think I was close to 30 years old before I told myself that I’m not a convict, I’m not an inmate, I’m not a prisoner, I’m a human being before I’m any of that. Having these conversations is what helped a lot of people think about the prejudice or the bias or the stereotype they might be holding onto and their perspectives about people who are currently or formerly incarcerated,” he said.

“If we can begin to step outside of our own preconceived notions and stereotypes, and try to put ourselves in another person’s shoes to better understand their position, that’s how we begin to heal. We’ll begin to understand. I’ll be able to see in you the same things I see in myself. It’s not until we start to have these dialogues and build rapport with one another that we’ll be able to identify ourselves in one another.”

Events like this one are so important because they bring community people who have never been incarcerated together with people who have — many of them for the first time. They show that the formerly incarcerated are people first and foremost and break down the myth that people are either victims of crime or people who cause harm. As these men show, the same person is often both at different times in their lives —because of trauma, the two are often interrelated. Once we get to know each other, and more importantly, stop fearing each other, we can start to work together to build the safe and thriving communities we all want to live in.

~Barbara Wieland

Communications Specialist