Safe & Just Michigan presents:

Life Beyond Life

The world agrees that children cannot be held to the same standard of responsibility as adults. A global consensus exists around the need for special protections for youth in the criminal justice system – yet the United States – and Michigan in particular – remains a shameful outlier in continuing to sentence youth to die in prison.

Stories of Life Beyond Life

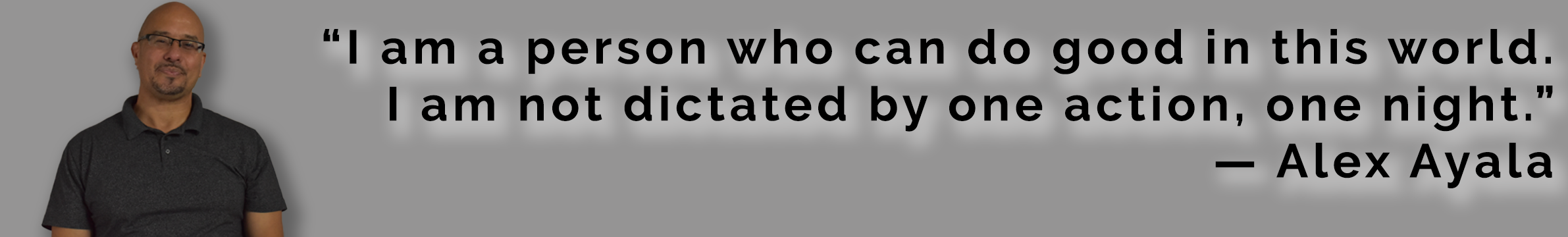

Alex Ayala

Alex Ayala grew up as a “military brat” — a child of a father in the military who was stationed at different bases around the world. After spending the first several years of his life in Puerto Rico, where his family was from, Alex joined his father in two deployments in Germany and one in Kentucky before arriving in Michigan around the time he turned 16 years old.

Moving around so often brought challenges for Alex. Looking back, he realizes that the frequent moves and losing friendships left him feeling insecure and craving acceptance from his peers. That left him vulnerable to falling in with the wrong crowd.

“When you do not accept your own self or who you are, you can get lost in other people,” he says.

A few months after arriving in Michigan, his newfound friends asked him to join them as they planned to rob a gas station. Since he was legally considered a child, his oldest friend told Alex and another friend his age to enter the store and rob it — that way, if they were caught, they would face a lighter punishment. Alex was given a gun, but he was nervous during the robbery and inadvertently fired it, hitting the gas station attendant, who later died.

Alex soon learned that juveniles can be charged, convicted and sentenced as adults — which his judge decided to do. He was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in prison with no chance of ever going home. Because he was still so young, however, it took Alex another five years to comprehend what a life without parole sentence truly meant.

Instead of giving in to despair, however, Alex chose a different path. He decided to educate himself — and others. He taught Spanish classes and bible studies. He reasoned that even if he couldn’t go home, perhaps he could reach others who would, and make sure they never came back to prison. And in the back of his mind, he never gave up hope that someone might realize he deserved a second chance, too.

His hopes were realized after the U.S. Supreme Court began rethinking juvenile life without parole sentencing in 2012. A series of rulings first made mandatory juvenile life without parole sentences unconstitutional, then applied that decision retroactively. Alex won a resentencing hearing and came home in 2019.

Since then, he has been working, spending time with family, traveling, mentoring and is active in his church. Unlike the teenager he used to be, he now feels secure in who he is. “One thing I do know is that I am Alex Ayala,” he says.

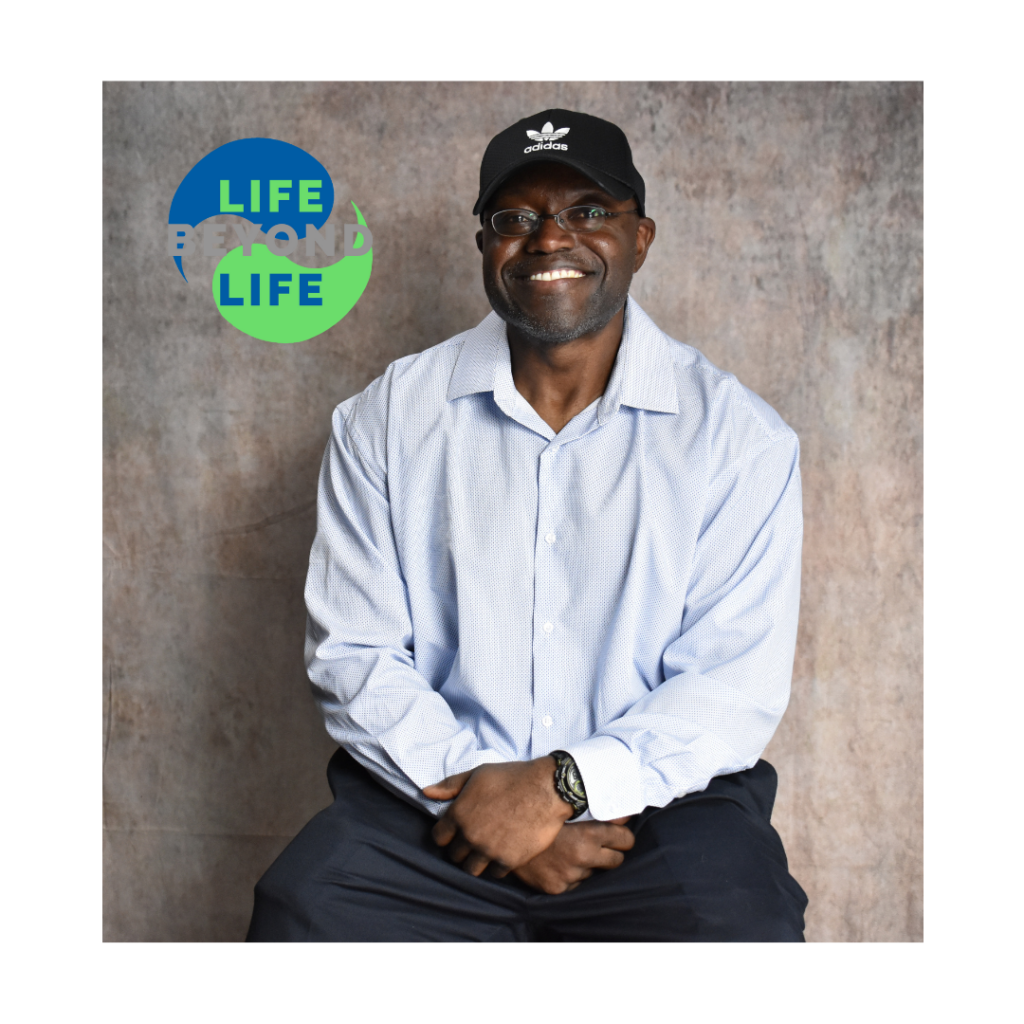

Barakah Sanders

Edward Sanders prefers to go by “Barakah,” a name that means blessings. He feels blessed even though he spent 40 years in prison for driving the car a friend fired a gun from, resulting in another person’s death. As one of Michigan’s youths sentenced to life without parole, a judge told him that he deserved to die in prison. But Barakah never agreed, and he never gave up hope that one day, he’d be free again.

Barakah grew up in Detroit in the 1960s and 70s. His neighborhood was dotted with notable people — he was friends with Aretha Franklin’s sons. In 1967, the Detroit Uprising took place on his doorstep, giving him a front-row seat to the violence and despair that can arise from inequality. As a teen, he became a leader of a street gang.

One night in 1976, he and his friends had a disagreement with another man as they drove past him. Barakah was the driver of the car. A passenger inside the car shot and killed the man. Barakah was arrested as an accessory and charged with felony murder, a charge that netted him a juvenile life without parole sentence, even though he wasn’t the one to shoot the gun.

In prison, Barakah took classes and earned a college degree. Then, he taught others. He became a leader and worked with organizations like the ACLU to end juvenile life without parole sentencing. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that these sentences could no longer be mandatory, he said he felt relief — even though the ruling didn’t immediately apply to him. It took a second Supreme Court ruling in 2016, which made the earlier ruling retroactive, to pave the way for Barakah to come home.

Since returning home in 2017, Barakah has earned a master’s degree in social work from the University of Michigan and has worked for the Washtenaw County Prosecutor’s Office in the Conviction Integrity and Expungement Unit. He sits on the Detroit Justice Center’s board of directors and aspires to go to law school.

“Learn to forgive even on your worst day,” Barakah urges.

Brandon Harrington

“Asked in one word to describe myself I would simply say I am a human.”

Brandon Harrington is quick to point out that he is one among many young people that have been sentenced to a “torturous, slow death” in prison. A permanent, unchanging sentence for a young person who has not yet reached the point in life where they mature and change.

“There are a lot of people you leave behind. You don’t see the difference between you and them. You just see them still stuck with that life without parole sentence without an opportunity to at least show rehabilitation over a period of 25 or 30 years.”

Brandon was born in Detroit to two parents that provided stability and “set a good example” for him. A studious child that loved books and astronomy, Brandon had trouble socially.

“I had an issue – I had a complex, a low self-esteem issue with my darker complexion. Most kids can deal with it and move on. Unfortunately for me, I couldn’t deal with it properly; I couldn’t process it.”

His social troubles led him to move high schools and find a new group of friends. Fed up with being “picked on, talked about, and laughed at,” Brandon joined a group he saw as well-respected and well-liked, his cousin’s gang.

Brandon quickly learned that in order to gain respect with his new peer group, his behavior had to become more and more anti-social. Brandon recalls, speaking of the night where at 17 he took the life of another young man:

“I thought that I was being exposed as a fraud for pretending to be somebody that I was not. It angered me – and to be blunt – it frightened me. I thought that I would lose my position, I would lose my association with this group, and I would go back to being just Brandon.”

It took Brandon years to understand the severity of his actions and the permanence of his sentence. Returning to his studious roots, Brandon took every educational, vocational, and behavioral course he could while incarcerated. Spending all his time in the law library, Brandon quickly cites all cases, codes, dates, and decisions affecting juvenile life without parole from memory.

“I don’t ever want anyone to hear me speak and not hear that from me.”

It is important to Brandon that whenever someone hears him speak on the injustice of sentencing children to permanent incarceration, that he acknowledges the hurt and pain they’ve caused.

“I took another young man’s life – an African American young man – who, to my knowledge, has both a daughter and granddaughter and they never had the chance to grow up with him. I took that away and that always has to be acknowledged.”

Since his release, Brandon has reconnected with his daughter, Brandy, the “light of [his] life,” and works as a commercial truck driver for a large distribution company, a future he could only dream of while taking reading-only CDL courses in prison.

Brandon has served as a peer-reentry leader for the Michigan State Appellate Defenders Office and continues to use his experience and legal knowledge to advocate for those left behind.

Craig Whilby

Craig Whilby appreciates the guidance he received as a child growing up in Detroit.

Craig’s mother died when he was an infant, but his father met another woman when he was eight years old, and she did her best to fill the role. His father was not much of a disciplinarian, but his stepmother was. She did a good job making sure Craig felt loved while pushing him to keep up with his grades and stay out of trouble.

Then, when Craig was 17 his father and stepmother split up. Craig lost his stepmother’s guidance.

One night, some of Craig’s friends picked him up and told him they planned to commit a robbery. Craig agreed to enter a home and help break into a safe. However, they were surprised to find that someone was home. One of the teens Craig was with killed the resident.

When Craig was arrested, he took responsibility for the role he played in the robbery but explained that he didn’t kill anybody. He was told he could be charged with murder because he participated in a felony that led to a person being killed, a possibility he couldn’t wrap his head around.

“I don’t think at 17 you really understand that concept,” Craig said. “You think ‘Well, I didn’t do the murder, how am I being charged with murder?’… You don’t really understand the laws.”

Instead of taking a plea deal, Craig decided to go to trial. He thought a group of 13 jurors would have more understanding for his case than a judge. But he was wrong, the jury convicted Craig and he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Craig never gave up hope that one day he would be free. He waited for his appeals and anxiously watched news stories about law changes, hoping something would apply to his case.

Through his 31.5 years of incarceration, Craig stayed hopeful. He found hope in just about everything, from positive interactions with corrections officers to building bonds with other incarcerated people to seeing his family when they visited.

“In order to survive the 31 years of incarceration, [you] have to have hope,” Craig said. “Every day you’ll wake up in a negative environment and could succumb to that negative environment.”

Finally, in 2019 Craig was released after a Supreme Court ruling that ordered all juvenile life sentences be reexamined.

Craig considers himself lucky because he had a friend who immediately offered him a job at his transportation company. With this job, Craig was able to provide for himself and with his friend’s guidance, eventually start his own transportation company.

Craig is working to make sure others have resources when they are released from prison as well. He helped start and co-directs a nonprofit called Friends of Returning Citizens (FORC) on a volunteer basis. FORC helps people with overturned juvenile life sentences return to living independently.

“Whenever we see a chance to help one another, we’re throwing it out there,” Craig said. “I think that support is so, so vital.”

He continued to say that many of the people who had juvenile life sentences overturned share his desire to use their remaining years helping others.

“We’re in our 50s… we might have 20 years left,” Craig said. “We’ve got to make our mark and do something positive.”

Daniel Jones

Daniel Jones left a large imprint on our lives. Sentenced to prison for life without parole at 17 for a killing he didn’t intend to commit, a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings gave him a second chance in 2019. In the three years he had as a free adult, he worked ceaselessly to register voters, reform the criminal justice system, bring comfort to people in distress, rehabilitate Detroit housing and even become a father for the first time. In his own words, he was a work in progress and a healer.

Daniel said he felt loved and secure in his family until his parents divorced when he was seven. Then, his mother became involved with a man who was addicted to drugs and who stole household items — and even their car — to feed his habit. It fueled an anger in Daniel that he didn’t know how to handle, so he avoided home. On the streets, he found kinship in a gang, not realizing that they didn’t have his best interests at heart.

One night, his friends picked him up with the intent to commit a robbery. Daniel didn’t even know how to fire the shotgun in the backseat — his friends taught him while they drove around town. Daniel panicked during the robbery and shot the weapon without aiming it. It tragically hit one of the people they were robbing, and the man died.

Because of his age, Daniel’s case could have been tried as an adult or a juvenile. The judge handling the case decided that Daniel was “incorrigible” and sentenced him to life without parole. In prison, Daniel took classes, read books on philosophy and psychology, and came to terms with the factors that led him to prison. He forgave and reconciled with his stepfather and found peace.

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court began rolling back laws on juvenile life without parole sentencing in 2012, Daniel had defied his sentencing judge by doing what he said was impossible: changing.

“I changed not because of prison,” Daniel says, “but in spite of it.”

Daniel came home in March 2019 and quickly won friends and supporters with his warm, genuine smile, his compassion and his unwavering dedication to criminal justice reform. He worked with organizations such as the Michigan Collaborative to End Mass Incarceration, the American Friends Service Committee-Michigan Criminal Justice Program and the National Life Without Parole Leadership Council. He also facilitated Safe & Just Michigan’s weekly support group for family members of incarcerated people.

A bullet ended Daniel’s life in November 2022, four months after he was interviewed for this video. The tragedy of his loss is compounded by the knowledge that Daniel himself would have given everything to help the person who shot him understand the futility of violence.

Gerald Merrel

Gerald Merrell knew about prison from a young age. The youngest of 14 siblings, he was only about 9 when one of his older brothers was sentenced to prison, where he later died under questionable circumstances.

His family already reeling from that loss, Gerald struggled as a youth. At 17, he and his friends were hanging out at a woman’s house when he was told that another man had touched his girlfriend. He and his friends decided to take the man home. While driving, Gerald’s friends told him he had to “do something” to the man or else he would look like a punk — and then they handed him a knife. When he hesitated, an older friend told him that if he didn’t do it, he would kill Gerald instead.

Terrified of what might happen and unsure how to stop it, Gerald did as he was told. “It was like a nightmare when I realized what I’d done,” Gerald said. Police arrested him a few days later. Gerald found himself housed in an adult jail. Later, he would be convicted in an adult court and sentenced to serve the rest of his life in prison without any chance of ever going home.

“It messed me up because I realized I would never get to see my family outside these bars again,” Gerald said.

Still, Gerald didn’t give in to despair. He realized that if the nation ever reconsidered juvenile life without parole sentences, he might have a chance to go home. With that in mind, he took care to avoid violations of prison rules and took educational and vocational classes so that he could make a strong case to go home — if he ever got a chance.

That chance came after the U.S. Supreme Court began re-evaluating juvenile life without parole sentences starting in 2012. That year, it banned mandatory juvenile life without parole sentences. Four years later, it made that earlier ruling retroactive, giving people like Gerald a chance to be resentenced.

Gerald went home in December 2020. Since then, he’s been working for an automotive manufacturer, spending time with his family and working with the State Appellate Defenders Office and the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth to end these harsh sentences for juveniles.

“To me, it’s a blessing to get a second chance,” Gerald says.

Lorenzo Harrell

Lorenzo Harrell largely had to figure things out on his own.

His grandmother did her best to pass along life lessons, but Lorenzo was raised by a single mother who was not ready to be a parent in a rough Detroit neighborhood.

“We kind of grew up in the wild, me and my sister,” Lorenzo said. “Basically, the streets raised us.”

Lorenzo grew up surrounded by violence and started selling drugs at just 13 years old. He said he remembers actions like stealing or vandalizing property were normal for kids in his neighborhood.

“When you live an abnormal life, you only want to feel normal and normal is defined by the people who are around you,” Lorenzo said.

When Lorenzo was 17, he, his cousin and another man became involved in an altercation that ended with Lorenzo shooting the other man. At the time, Lorenzo did not understand the seriousness of what he had done.

“My mindset at the time was it really doesn’t matter, I don’t care,” he said. “I just hate it that I had that mentality at that time,”

Lorenzo was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. For years, he could not comprehend spending the rest of his life locked away from society.

“The older guys, they knew what was going on,” he said. “But my peers, we just wanted to play basketball, we wanted to lift weights, we wanted to do everything attributed to keeping our mind off what we were going through.”

Lorenzo said at around 25, the reality of the life sentence started to set in, and he fell into a depression. It was also around this time that Lorenzo started to realize the harm he’d caused. His thoughts constantly gravitated back to his victim, a tendency that continues to this day.

“I really wish I could bring this guy back,” he said. “Even if it [meant I] sacrifice myself, I wouldn’t have a problem with that.”

Eventually, Lorenzo started working in the prison’s law library. There, he learned to transcribe braille—a skill that serves him to this day.

“I’m just so fortunate that I had people around that saw me for more than what I was in there for,” Lorenzo said.

Following a Supreme Court ruling that required all juvenile life sentences be reviewed, Lorenzo was released in February of 2019. Today, he works for Michigan State Appellate Defender Office, where he transcribes braille for blind people, a profession he loves.

“That braille profession has done so much for my life, and even for other people’s lives because I’m able to help more people,” he said. “I’m just so appreciative for that. I’m just blessed.”

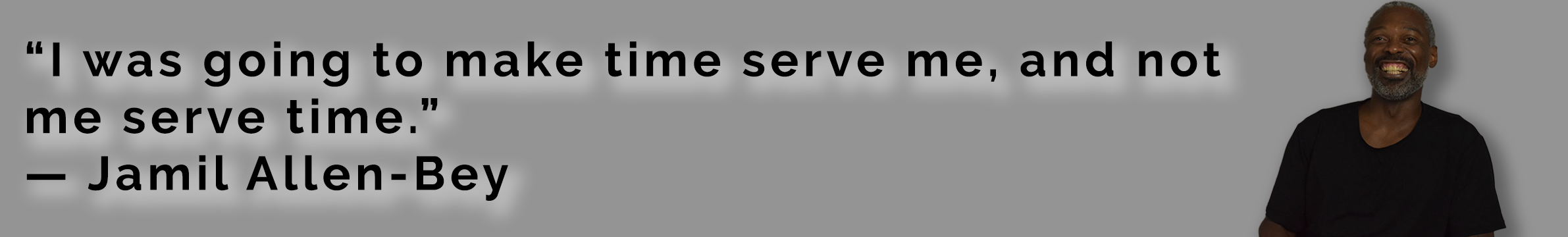

Jamil Allen-Bey

At 17, Jamil Allen-Bey couldn’t read the important papers before him — papers that would change his life. Education hadn’t been an emphasis in his young life, which had been full of violence and tragedy. His mother had been incarcerated for assault, and his aunt had been killed by her husband. Now, Jamil was about to come before a judge.

Besides the proceedings in the courtroom, there were stacks of paperwork to go through. Jamil, who had dropped out of school after being diagnosed with a learning disability in ninth grade, couldn’t understand what was put before him — papers that said that even though he was still a teenager, he faced the possibility of being sent to prison for the rest of his life with no chance of ever coming home.

He faced trial because an attempt to help his family had gone tragically wrong. An uncle asked him to help a cousin who was being bullied by a gang member. Jamil had intended to fire a warning shot over the head of his cousin’s bully, but the man was getting up from a sitting position just as the gun was fired. As a result, Jamil had shot and killed him.

Jamil was ultimately convicted and sentenced to live out the rest of his life in prison. But it took several more years for him to truly understand that he was meant to die in prison, too.

Instead of giving up, Jamil became inspired by a mentor he found in prison and decided to learn to read. He earned his GED and went on to read stories of enslaved people and others who had obtained freedom. He realized education was key to freedom, so he doubled down and challenged himself to learn more. He wanted to learn why he made the choices he did and how he could improve himself.

Key to his transformation, Jamil decided he had to reparent himself — to give himself the nurturing he didn’t get as a child.

Once the U.S. Supreme Court made it possible for people sentenced to juvenile parole to be resentenced, Jamil came home in 2018. Today, he works at a warming center for people experiencing homelessness in Detroit.

“I believe our purpose here on this earth is to serve and to make life better for the generation to come,” Jamil says.

Jose Burgos

Jose Burgos’ childhood was idyllic: he loved exploring nature in the backyards of Detroit and going to school. But everything changed when his mother passed away when he was just 13 years old. Suddenly, Jose — who never knew his father — couldn’t concentrate at school and lost interest in the things that used to fascinate him. He dropped out of school in the 7th grade, and looking for a place to fit in, he turned to gangs.

Instead of learning about insects and reading books in libraries, he now learned about violence in the street.

Jose was 16 years old when he attempted to swindle twin brothers in a drug deal by filling a bag with rags instead of marijuana. He was in the back seat of the men’s car when one suggested they check what was inside of the bag. He saw one moving around in the seat in front of him and thought they may be reaching for a weapon. Jose panicked and shot both men, killing one and leaving the other paralyzed from the neck down.

Jose was just 17 when he was sentenced to life in prison. He said it took years for him to understand the gravity of the harm he had caused, but once he did, it transformed him. He wanted to spend the rest of his life to make amends for it, even though he had been told he would never come home from prison. And that meant he had no room for despair.

“I always wanted to keep my mind healthy,” he said. “Keeping my mind healthy was always having some type of hope.”

Following a 2016 Supreme Court ruling that ordered juvenile life sentences be reviewed, Jose was released in 2018 after serving 27 years.

Today, he works for the Michigan State Appellate Defender Office helping incarcerated people before and after their sentences end with reentry.

“If they need help, I don’t know where I’m going to find it, but I’m going to find it for them,” Jose said.

The guilt from his actions at 16 will never go away. However, Jose uses his past as motivation to help others today.

“It never goes away, it’s something that, for me, is something that drives me,” he said. “I wanted something good to come out of such a bad situation.”

Kyle Daniel Bey

Growing up, Kyle Daniel-Bey felt like an outsider. He and his two younger sisters were the only Black children in their elementary school in Vermont. Later, when their family returned to Detroit, he was picked on again because he was from the country.

Tired of not fitting in, Kyle did what many other young people around him did — he turned to a street gang for a sense of belonging. Instead of acceptance, he found violence, tragedy and ruined lives. Convicted of a killing that took place when he was 17 years old, Kyle was sentenced to prison for the rest of his life without any chance of going home, making him one of Michigan’s juvenile lifers.

Then, fate intervened.

A series of U.S. Supreme Court cases rethought juvenile life parole sentences for people under 18, opening the door for Kyle to be resentenced. Today, he is working as an iron worker and looking at getting into real estate. He’s also a father and grandfather, but most importantly, he says, “I’m a good dude, and there’s nothing wrong with being a good dude.”

Kyle’s family moved to Vermont when he was an infant because his father got a job there. Growing up as one of few non-white people in a state where 95.6 percent of the population is white was a challenge. Some kids at school taunted him and his sisters for looking different, and things got so bad that Kyle began taking knives to school to protect them. The situation was intolerable, so his family moved back to Detroit.

Living in a neighborhood hit hard by the crack epidemic, Kyle was then targeted because he grew up in a rural setting and for being serious about school. The loneliness got so bad that he became suicidal.

“I was a nerd who didn’t value being a nerd,” he said. “I was tired of fighting, tired of feeling like a loner, and tired of feeling like no one understood me.”

Kyle thought he finally found camaraderie in a street gang and he left school. When he was 17, he shot a man from a rival gang during a confrontation. His court case dragged on for years and resulted in being sentenced to prison for the rest of his life.

One of the hardest parts of receiving such a hard sentence was leaving behind a young daughter. He wouldn’t see her again until he was getting ready to go home and she was 30 years old.

Kyle spent his time incarcerated taking all the vocational and educational classes he could get into. In this way, his prison experience was similar to those of many other juvenile lifers’ experiences, Kyle said.

“Yes, we all came in and acted a fool. Some of us took longer than others, but we all settled down, we all developed. We all turned into — not model prisoners, because we weren’t trying to be model prisoners — we were trying to be good people. And good people, no matter where they find themselves, try to do good things.”

Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court began to understand that it is a mistake to send children to die in prison. In a series of decisions, it banned mandatory life without parole for juveniles, then made that decision retroactive, creating a path for people like Kyle to come home. He finally did in September 2018.

Since then, he’s earned an associate degree from Wayne County Community College and works as an Ironworker. He’s bought his first house and reconnected with his daughter and grandchild. His plans for the future include helping people coming home from prison find safe and affordable housing.

He also wants to change the way people see people like himself: people once sentenced to die in prison while they were still children.

“We need to make the distinction on the people we’re punishing between the people we’re afraid of and the people we’re mad at. Children are different,” Kyle said. “You don’t hold children to an adult standard when most adults can’t hold themselves to that standard.”

Machelle Pearson

When Machelle lost her mother as a pre-teen, she didn’t just lose a parent. She also lost her provider and protector.

“I had a good childhood when she was living,” Machelle said. “It changed when she left.”

Machelle’s father struggled with addiction and was not equipped to care for her or her many siblings. A child not old enough to care for herself, Machelle promised her mother to look after her siblings the best she could.

After her mother’s passing, Machelle bounced around between foster homes and living with family. In the process, she endued cycles of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.

Eventually, Machelle began staying with an abusive boyfriend and became dependent on him. One day, her boyfriend and his brother planned a robbery and gave Machelle an impossible choice: She could help them, or they would kill her younger brother. Machelle remembered the promise she made to her mother and agreed to assist the pair. They gave her a gun and told her to ask strangers for a ride. Her boyfriend and his brother would follow the car that picked up Machelle to commit the robbery.

A woman agreed to give Machelle a ride, but Machelle couldn’t follow through. Machelle revealed the robbery plot and tried to hand the gun to the woman. But Machelle had never handled a gun before, and in her panicked state, she accidentally discharged the weapon. The bullet went through the woman’s neck, killing her.

Machelle received a life sentence without the possibility for parole for a mistake she made as a child.

Machelle never gave up hope she would be free again and following a Supreme Court ruling that ordered life sentences given to juveniles be reviewed, Machelle was released in 2018. Machelle was released to a whole new world with a whole new set of challenges that she is still learning to navigate.

“Because I have a felony, I couldn’t even scoop ice cream,” she said.

But Machelle has a “guardian angel” who is helping with her reentry. An alternate juror for her case was moved by her story and kept in touch during her prison stay. She and her husband have helped her find housing and stability since her release.

This allows Machelle to follow her passion and help adolescents who find themselves in situations similar to her own. She regularly talks to kids at risk of heading down the wrong path and young women who have been abused.

“I feel like that’s what I’m here to do, is pull youth, even grown people out of abusive relationships,” she said. “Let them know where it led me because I didn’t have guidance.”

Malachi Muhammad

Asked to describe himself, Malachi Muhammad will tell you that he’s a believer. He believes in the ability of people to change and the need for second chances. He is also a student of the Nation of Islam. But he doesn’t describe himself with titles like advocate or mentor, even though he takes on both of those roles.

“I use the word ‘believer’ because it doesn’t put me in a box,” Muhammad explains. And after being in prison for 29 years, he’s had enough of that.

Muhammad is one of Michigan’s former juvenile lifers — someone who was sentenced to life without parole while they were still a teenager, but who has since come home thanks to subsequent Supreme Court rulings that found mandatory life for juveniles to be unconstitutional. Bills pending in Michigan would ban discretionary life without parole for juveniles as well.

Muhammad life changed when he was 15. First, one of his aunts was killed by her husband. The following year, his great-grandmother — who he lived with — passed away from a heart attack. As a result, he was sent to live with his grandparents on the city’s west side, a place where he didn’t feel he fit in.

Soon, he became involved with people who sold drugs. That led to a plan to rob someone of his drugs, but the plan went wrong. Muhammad wound up shooting and killing the man.

“Your life can change in that quick of a second, and you can’t take it back,” Muhammad said.

Muhammad entered prison at 17 and learned what it meant to be incarcerated for natural life when others told him he was going to die there. Rather than give up or get angry, Muhammad decided he must improve himself.

He found support and inspiration from Islam, a faith he discovered while incarcerated. Asked to deliver a speech for the solemn holiday of atonement in 2013, Muhammad understood that he must first make his own atonement. He stopped referring to himself as innocent and began to take full accountability for the actions that led to his incarceration.

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions rethinking juvenile life without parole led to Muhammad’s resentencing hearing, even the mother of the man he had shot saw a change in him. She told the judge that she believed Muhammad had learned his lesson and deserved a second chance.

Muhammad was released in November 2019.

Since then, he has been working and volunteering as a community outreach worker for the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office, where he helps people in the county jail prepare to transition home, and as a mentor for people on probation. He’s also a trauma informed peer led reentry navigator for A Brighter Way in Washtenaw County.

Muhammad points out that both science and faith now agree that youth deserve second chances. The most recent studies in brain development suggest that human brains aren’t fully developed until the age of 25, and younger people don’t have the same ability to think through decisions as adults. And all faith traditions relate the importance of redemption and second chances.

“Get to know us,” he urged. “Get to know the criminal justice system. It’s flawed in so many ways.”

Ronnie Waters

Born in Nashville, Tennessee – because his hometown hospital did not accept Black patients – Ronnie Waters was a fun-loving child. The youngest of four, Ronnie has always held deep respect for his mother’s drive to care and provide for him and his siblings despite her limited education and, therefore, earning power.

“Hard working woman, Christian woman, who was devoted to her kids,” Ronnie recalls. “She always found a way to support us.”

Following his parents’ divorce, Ronnie’s mother moved him and his siblings to Pontiac, Michigan where they lived with his grandfather. After years of struggling working low wage jobs in Pontiac, Ronnie’s mother was hired at General Motors. This significant wage increase afforded her the opportunity to move the family into a house of their own in an allegedly better neighborhood. The move did not help Ronnie’s confidence. Describing himself as an insecure kid, and lacking the structure, attention, and close monitoring he knew he needed, Ronnie felt deeply the pressure to prove himself to his trouble-seeking peers.

“It was a lot of peer pressure to prove your worth…and we thought it was manhood if you accepted those challenges.” He remembers being “scared to death” but accepting the challenges his peer group put forth anyway.

Having participated in relatively minor juvenile delinquency since his move, Ronnie thought the night of May 3, 1980 would be no different.

“This is the first time I ever carried a gun, ever in life carried a pistol,” recalls Ronnie.

Remembering his friends shooting this same .22 caliber gun at abandoned cars and the bullet not penetrating the windshield, Ronnie mistakenly believed his shot fired at the passenger side window of a car while at a drive-in movie theater would be no different. The bullet penetrated the passenger window, killing the woman inside.

Ronnie was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole at age 17.

“I’ve only been on this earth for 17 years; so, life to me was 17 years,” he says adding that as a juvenile he was clearly not able to make good decisions or grasp the gravity of the situation. When he realized the pain he had caused, that he “took a life” his mind and body went numb.

In the 40 years that Ronnie spent behind bars, he has developed mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Never believing that he would die an incarcerated man, he took every opportunity to better himself. He dug into and faced his remorse, took every class and job skills training available to him, earned an associate degree in arts and sciences, and shared the support his family gave him with the less fortunate men he met in prison.

Ronnie was afforded a second chance following the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court case that banned mandatory life without parole for children, Miller v Alabama. Ronnie was resentenced and released in 2020. He has spent every moment since advocating for those he left behind.

“I’m not exceptional,” Ronnie shares emphatically. “I know that it’s so many other people who I left behind that are capable, or more capable than me, of coming out here and doing the same things I’ve done…I use myself as an example of what you should be doing when you receive a second chance and I’m not an exception.”

Ronnie now serves as Community Engagement Specialist with Safe & Just Michigan and lives with his high school sweetheart and wife outside of Detroit.

Juvenile Life Without Parole

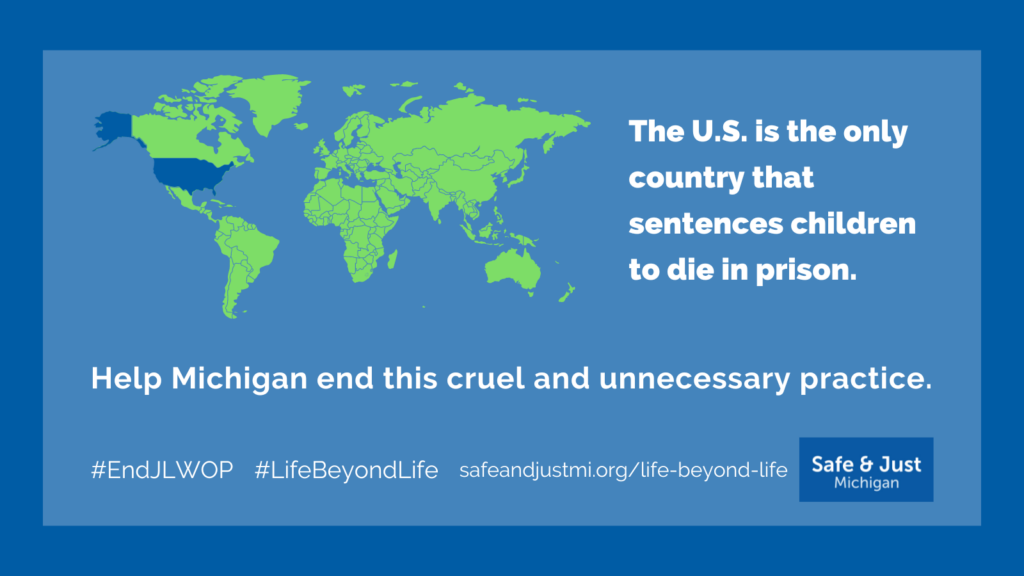

The United States is the only country in the world that sentences children to die in prison. The practice, known as juvenile life without parole (JLWOP), is prohibited under numerous international laws including the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Yet twenty-five U.S. states still permit this sentence – and Michigan houses the second largest population of people serving juvenile life without parole in the nation.

In four decisions – Roper v. Simmons (2005), Graham v. Florida (2010), Miller v. Alabama (2012), and Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) – the Supreme Court of the United States established and upheld the fact that “children are constitutionally different from adults” in their level of culpability and capacity for change. Ruling it morally and constitutionally wrong to equate offenses committed by emotionally undeveloped youth with crimes carried out by adults.

While these decisions did away with JLWOP as a mandatory minimum, the sentence remains discretionarily legal in the “rare” case that a child is beyond all hope of redemption. Twenty-five states and D.C. have since banned the practice, seven states have no one serving life-without parole sentenced as a juvenile, and many of the remaining states quickly resentenced those that were. Michigan, however, has resisted the world and the highest court in the land’s rulings, claiming that 55 percent of its more than 350 people sentenced under the age of 18 to life without parole are irredeemable.

Research shows that adolescents have not fully developed the parts of the brain responsible for impulse control and understanding consequences – it’s the reason we don’t let youth drive, make decisions related to their medical care, vote, or sign contracts. They’re not capable of navigating the legal system and often receive harsher punishments than their adult codefendants.

These same developmental differences make youth uniquely capable of rehabilitation.

Locking up a child and throwing away the key is unjust as they’re fundamentally incapable of the same level of guilt as an adult, not deterred by harsher punishments because of their inability to connect actions to consequences, denied any chance at rehabilitation, and the practice doesn’t make communities safer – data shows nearly all youth will age out of crime.

Not just inhumane, t’s incredibly expensive. The 2022 MI Supreme Court decision extending the ban on mandatory JLWOP to individuals under the age of 19 – brings our state’s total number of youth sentenced under this scheme to nearly 700 people. If nothing changes, Michigan will spend an estimated $2.04 billion incarcerating just this population alone – this population of youth that will statistically age out of crime. Not only is incarceration expensive, but Michigan pays for both sides of their unnecessarily complicated resentencing process, costing taxpayers an average $2 million per year.

The consensus is clear, sentencing children to life without parole is cruel, unjust, and unnecessary. It is time Michigan joined the rest of the world in giving youth a second chance.

Facts and Shareables

Did you know?

- 25 states and DC have banned juvenile life without possibility of parole.

- 7 other states currently have no one serving JLWOP sentences.

- Michigan houses the nation’s second largest population of individuals serving life without parole sentenced as youth. It is the leader in individuals serving life without parole per capita.

- Decades of research support the conclusion that youth are less capable than adults in impulse control, resisting outside influence or peer pressure, and understanding the consequences of their actions; and that are uniquely capable of rehabilitation.

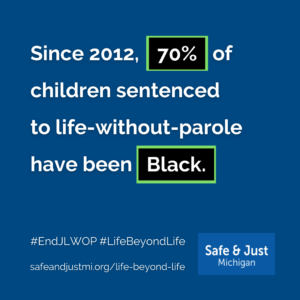

- African American juvenile offenders are sentenced to JLWOP at almost twice the rate of white juvenile offenders per homicide arrest.

- In Wayne County, Black youth represent 90% of juveniles that receive life without parole sentences while only accounting for 41% of the overall population.

- Clear geographic disparities in JLWOP sentencing exist within Michigan. Oakland, Calhoun, Saginaw, and Kent Counties offer lessor sentences to youth at significantly lower rates than the state average. Wayne and Oakland Counties account for 9% of all JLWOP sentences in the nation.

- Juveniles reject plea offers at much higher rates than adults; therefore adults receive lessor sentences for comparable crimes. Juveniles are less equipped to negotiate plea offers because of their immaturity, inexperience, and failure to realize the value of a plea deal.

- Race seriously affects the plea bargaining process for adolescents. Youth accused of a homicide offense where the victim was white were 22% less likely to receive a plea offer than in cases where the victim was a person of color.

Help End this Unnecessary Practice NOW!

In 2022, legislation was introduced in Michigan to end the practice of sentencing juveniles to life without the possibility of parole. The work to pass that proposal will continue into the 2023 legislative session.

Share Life Beyond Life storyteller sessions, facts, and pre-made graphics on your personal and business social media pages. Help send the message to Michigan lawmakers that sentencing children to die in prison is not only a cruel and outdated practice, but a waste of taxpayer funds as it does nothing to make communities safer.

#EndJLWOP #LifeBeyondLife @safeandjustmi

“There is a misconception that Miller v. Alabama ended juvenile life without parole for good, but it did not. States like Michigan can still sentence children to death by incarceration.” | Ronnie Waters, Safe & Just Michigan Community Engagement Specialist, sentenced to life without parole as a juvenile, released in 2020 after a resentencing hearing.

“We understand the severity of our actions, we also understand who we are as people. We are children. We have a lot of trauma we’re dealing with and we just don’t know how to process it. That does not excuse or justify any behavior but should mitigate at sentencing.” | Brandon Harrington, advocate, commercial truck driver, paralegal, and father, sentenced to life without parole as a juvenile, released in 2021 after a resentencing hearing

Help Michigan join 32 other states and D.C. in ending the practice of sentencing children to life in prison without the possibility of parole!