(This is the first post in a series Safe & Just Michigan is running on Michigan’s habitual offender laws.)

(At Safe & Just Michigan, we generally use human-centered language. However, to keep technical concepts clear in this blog post, we will adhere to legal terminology, which is unfortunately not human-centered.)

A new senate bill package has the potential to change how habitual sentencing enhancements are applied in Michigan. At the beginning of January, state Sens. VanderWall (R-Ludington), Irwin (D-Ann Arbor) & Santana (D-Detroit) introduced a bill package to reform habitual sentencing in Michigan. The application of habitual sentencing enhancements is a matter of discretion for prosecutors which varies greatly. The status can be applied to a person who has been convicted of a prior felony, even if the prior conviction is unrelated to the current offense or was long ago and can result in an increased sentence.

Senate Bills 697-699 aim to address several issues that would change the application of the habitual status sentencing enhancement. Senate Bill 697, introduced by Sen. VanderWall, addresses the application of fourth habitual offenders, which applies to people who have at least three prior felony convictions, and can double the maximum sentence. SB 698, introduced by Sen. Irwin, addresses the application of third habitual offender to people who have at least two prior felony convictions, which can increase the maximum sentence by 50 percent. Last, SB 699, introduced by Sen. Santana, addresses the application of second habitual offender sentencing enhancements, which apply to persons who have at least one prior felony conviction, and can increase the maximum sentence to be served by 25 percent.

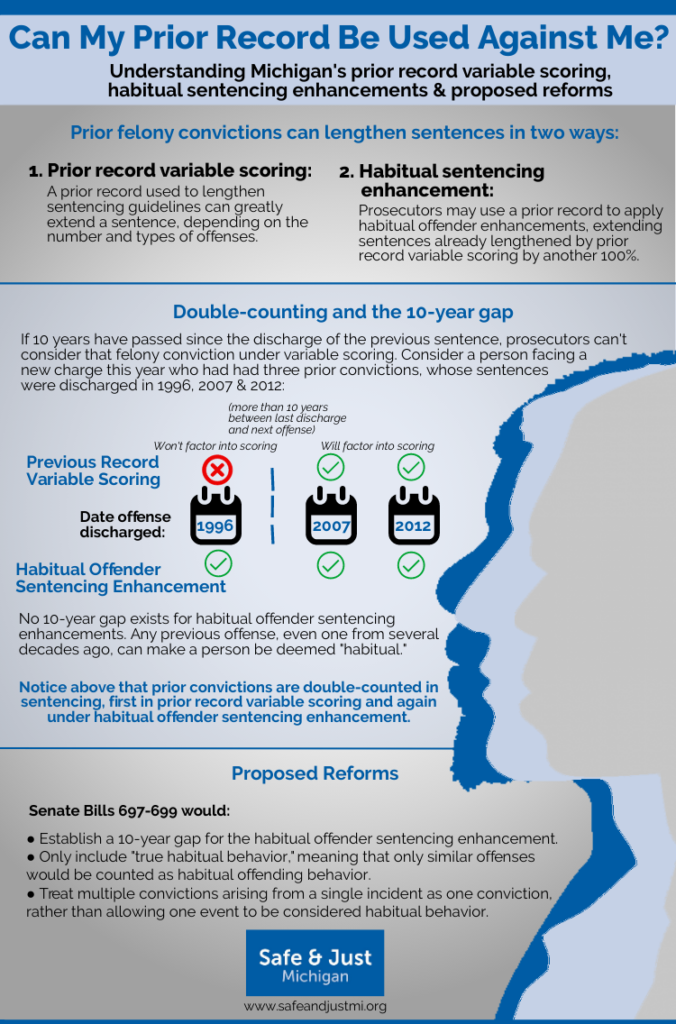

In each of the bills, parallel changes are proposed to modify who is eligible and how prior convictions can be applied. One of the issues to be addressed is the double-counting of prior felony convictions. This issue was highlighted in the Council of State Government Justice Center report, “Compilation of Michigan Sentencing and Justice Reinvestment Analyses,” released in 2014. When a prosecutor decides to charge someone as a habitual offender, their prior convictions are counted against them twice. First, they are considered in the scoring of the prior record variable (PRV) for the sentencing guidelines. Then, their prior convictions are again used to determine their habitual status.

The example below visualizes how prior convictions are double-counted when a habitual status enhancement is applied:

Included in the example above is the “10-year gap,” which only applies to prior record variable scoring. The 10-year gap pertains to a cut-off point that occurs when a person accrues 10 years without a conviction after the date of their last discharge from prison, parole, probation or another sentence. Once that occurs, a prosecutor can no longer include their record before that point among the factors considered in their prior record variable scoring, which can have a serious effect on the length of a sentence.

For instance, consider the example of a man discharged from prison in 2010 after serving a maximum sentence. If he was convicted of a second crime occurring in 2019, the judge must consider that earlier conviction as a factor in sentencing under prior record variable scoring. That changes if he were convicted of a crime occurring just one year later, a decade after his prison release. In that case, since a decade has passed since the discharge of his most recent sentence, his prior conviction could not be factored against him in variable scoring. These scores can add months or even years to a sentence.

However, no such 10-year gap exists when it comes to habitual enhancements, which prosecutors can use or not use at their discretion. Prosecutors can consider any conviction, no matter how long ago it happened and no matter how long a person may have gone without having any involvement with the law in between. If a person was convicted of vandalism as an 18-year-old and then was convicted of robbery in their 40s, that conviction as a teenager could be used to make them a “habitual” offender.

The reform bills in Lansing would change that by introducing the 10-year gap to habitual offender enhancements, bringing them on-par with prior record variable scoring.

Another proposed modification of the sentencing enhancement is to only include “true habitual behavior.” Meaning only similar offenses will be counted in the number of priors included in the determination of habitual offending behavior. Additionally, as explained in this prior blog, changes included in the bills is to stop the penalization of “one bad night”. If multiple convictions result out of one incident, they are currently considered multiple events under the habitual offender statute. The proposed changed would require convictions arising from a single incident to be treated as only one conviction.

The last proposed change applies only to the fourth-offense habitual status. Currently, there is a 25-year mandatory minimum for serious fourth habitual offender convictions. Eliminating the mandatory minimum sentence would allow judges discretion to determine the length of sentences imposed depending on individual circumstances.

Habitual offender status sentencing enhancements increase the length of thousands of prison sentences each year. The proposed changes to habitual sentencing won’t eliminate habitual sentencing. However, they will take steps toward reducing disparities in the application of habitual status. Safe & Just Michigan supports these reforms and future blogs will further explore the application and impact these sentencing enhancements have on the people incarcerated in Michigan prisons.

~Anne Mahar

Research Specialist