The Michigan Department of Corrections has released its 2019 Statistical Report, offering a glimpse into Michigan’s corrections system shortly before the COVID-19 crisis took hold and brought about some significant changes. Some of those changes are visible in a subsequent report to the Michigan Legislature in a January 2021 Budget Briefing document that detail how the state’s prison population dipped precipitously because of the pandemic.

Aside from financial information, which follows a fiscal year that ends June 30, the numbers in the 2019 Statistical Report generally reflect numbers as they stood on Dec. 31, 2019. At that point in time, COVID-19 was yet unnamed and the U.S. was 19 days away from its first diagnosed case. Michigan’s first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed on March 10, followed a week later by the first case of a person incarcerated in a Michigan prison diagnosed with the virus.

That diagnosis drastically changed life for people who live in Michigan prisons. Already by March 13, 2020, all visitation at Michigan prisons came to a halt. Waves of infection began to wash over one facility after another, sometimes resulting in nearly all of a facility to become infected. The first death among people incarcerated in Michigan prisons occurred in Jackson on April 1, when 55-year-old Joe Louis Kearney was found unresponsive in his cell. To date, another 138 lives have been lost among Michigan’s incarcerated population. They include William Garrison, a man who had served 44 years and was awaiting his imminent release when he became sick.

Safe & Just Michigan — along with other criminal justice reform advocates, including the ACLU-Michigan, AFSC-Michigan Criminal Justice Program, Detroit Justice Center and individuals from around the state — began calling on Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and MDOC Director Heidi Washington to follow CDC guidelines and releasing people who posed no public safety threat to allow for social distancing. While some were released — as reflected in the statistic book — it was not enough to stop the ongoing crisis.

Numbers don’t lie — but there’s more to the story

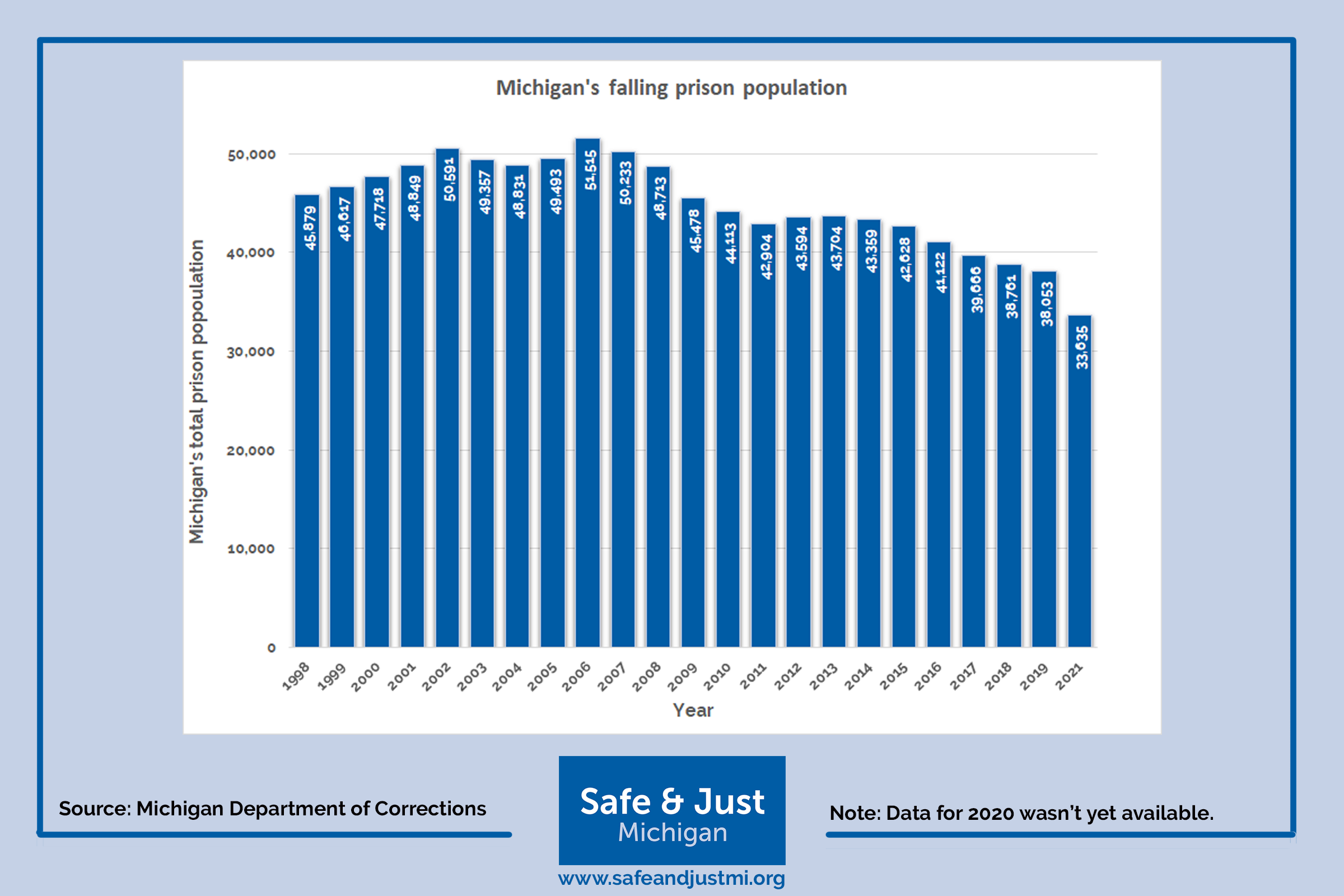

According to the MDOC 2019 Statistical Report, Michigan’s prison population had been falling long before COVID-19 entered the scene, and 2019 was no different. As of Dec. 31, 2019, the state had 38,053 people incarcerated in the state’s prison system, a 1.8 percent dip from where it stood at the end of 2018, but a 26.1 percent drop from 51,515 — the highpoint of the state’s prison population, reached in 2006.

Then came COVID. By January, 2021, the state’s prison population had fallen a more dramatic 11.6 percent drop in just one year — to 33,635 compared to 2019’s 38,053 people. The drop is even more breathtaking when you compare it to the 2006 watermark. Compared to then, our state’s prison population has shrunk a whole 34.7 percent.

Then came COVID. By January, 2021, the state’s prison population had fallen a more dramatic 11.6 percent drop in just one year — to 33,635 compared to 2019’s 38,053 people. The drop is even more breathtaking when you compare it to the 2006 watermark. Compared to then, our state’s prison population has shrunk a whole 34.7 percent.

While those numbers look good — and they are — it would be premature to celebrate Michigan’s rapidly declining prison numbers. For one, many of those falling numbers represent one-time events rather than true policy changes that can be sustained over time. For instance, in early June 2020, the MDOC reported that the prison population had dropped 5.2 percent over three months because of paroles, decreased intake from county jails and courts and fewer people being returned to prison for parole violations. Of those, MDOC spokesman Kyle Kaminski said the decrease in transfers accounted for about half of the decrease. Later in the year, it became evident that the number of people paroled throughout 2020 was actually lower than the number of people paroled in 2019.

Time will tell for certain, but it’s dubious whether the precipitous drop in the prison population seen between the end of 2019 and January 2021 can be sustained. The number of people transferred to prison will likely increase again once health concerns are decreased — and that accounted for half of the population decrease as of June 2020. However, one new law passed in Michigan in 2020 is intended to tailor parole terms to individuals so that fewer are returned to prison on technical violations, so that may result in a sustained lowering of the prison population. Safe & Just Michigan will continue to keep a watch on the prison population and reasons for its increases or decreases.

Prison stays get longer, health costs keep climbing

More troubling, the MDOC 2019 Statistical Report shows that the average length of a prison stay continues to grow. In 2019, the average minimum length of a prison sentence was 10.8 years, a 1.9 percent increase from the average stay of 10.6 years in 2018 but a 28.6 percent increase from a decade earlier, when the average minimum sentence length was 8.4 years.

This suggests that more people are being sent to prison for long stays — and the numbers bear that out. In 2019, the MDOC counted four more people serving a minimum sentence of 20 years compared to 2018 (2,586 compared to 2,582 people); 39 more people serving a minimum sentence of 25 years (2,222 people in 2019 compared to 2,183 in 2018); and 79 more people serving a minimum sentence greater than 25 years but less than life (2,861 compared to 2,782). Interestingly, the one exception to that trend was the number of people serving life sentences, which saw a decrease of less than 1 percent from 5,056 in 2018 to 5,017 in 2019.

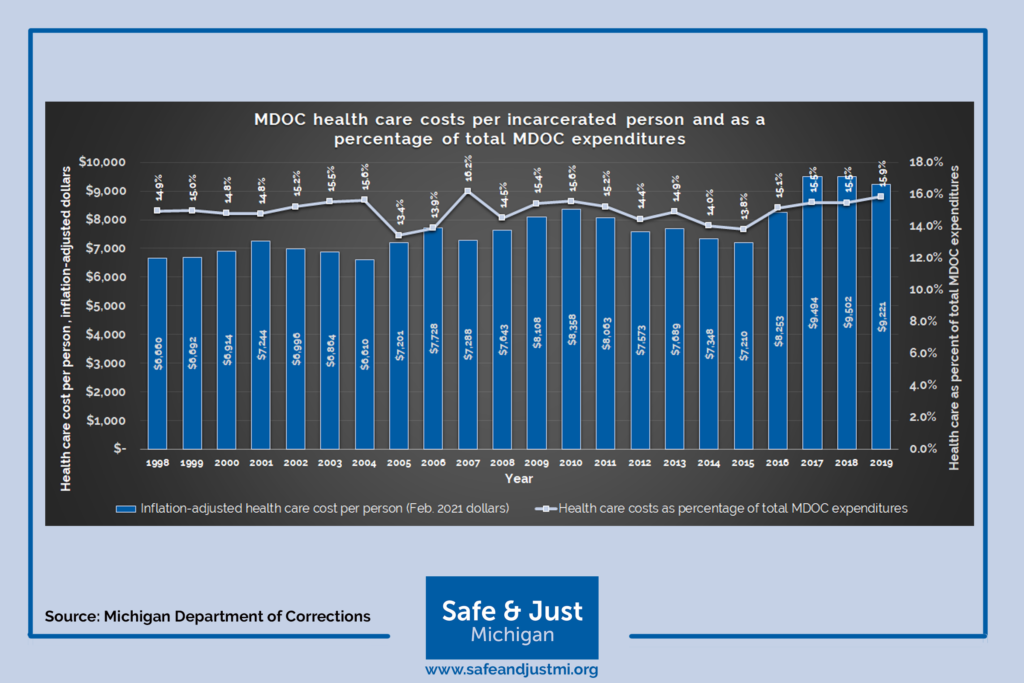

The increasing length of prison stays has several important ramifications. Long sentences — and especially life sentences — are correlated to an aging prison population, and aging populations often bring higher medical costs. We can see that in the average medical expenditure per person incarcerated. Using figures adjusted for inflation as of February 2021, the average health care cost per person in 2019 was $9,220.75 — a modest decline of 3 percent compared to the health care cost per person of $9,501.60 in 2018. However, compared to a decade ago, health care costs have climbed 13.7 percent from $8,107.86 in 2009.

The increasing length of prison stays has several important ramifications. Long sentences — and especially life sentences — are correlated to an aging prison population, and aging populations often bring higher medical costs. We can see that in the average medical expenditure per person incarcerated. Using figures adjusted for inflation as of February 2021, the average health care cost per person in 2019 was $9,220.75 — a modest decline of 3 percent compared to the health care cost per person of $9,501.60 in 2018. However, compared to a decade ago, health care costs have climbed 13.7 percent from $8,107.86 in 2009.

It’s still too early to know what sort of effect the COVID-19 crisis will have on the health care cost per person, but we’ll be watching for that information in upcoming reports.

The growing sentence length also points to the need to confront more difficult points of criminal justice reform. So far, most new policies have dealt with nonviolent offenses that bear short prison terms. These legal changes often find broad popular support. However, getting the public — much less lawmakers — to sign on to criminal justice reforms that involve violent offenses will take more effort. It’s work that Safe & Just Michigan is ready to do.

Women in prison

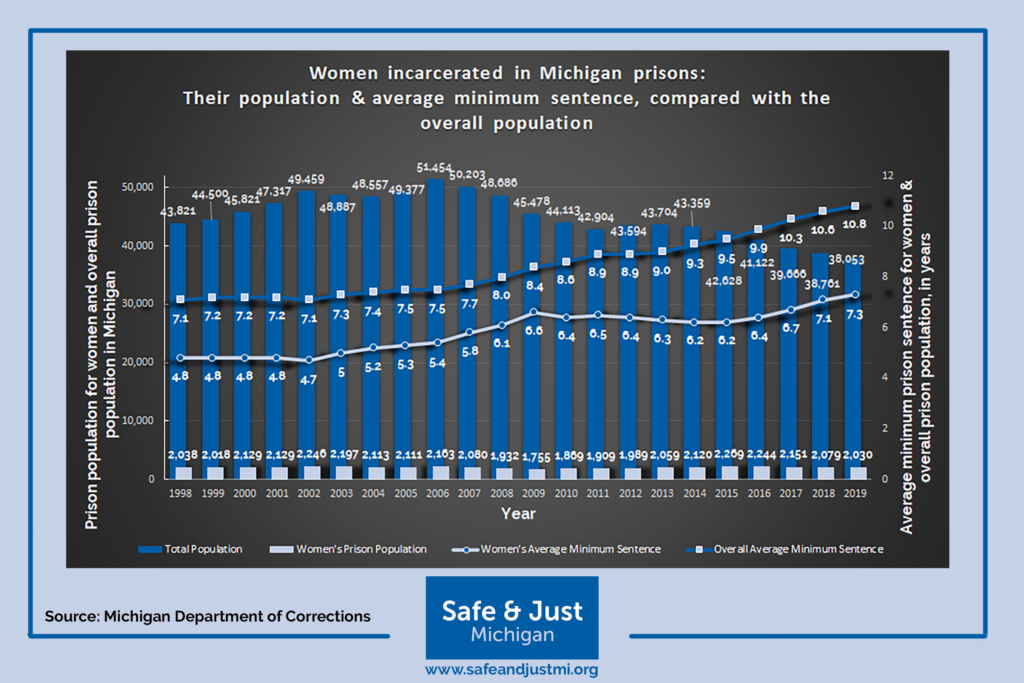

Women continue to comprise a small fraction of the overall prison population in Michigan — 5.33 percent in 2019, virtually unchanged from the 5.36 percent they represented in 2018. Even so, they have singular issues that deserve attention, and statistics regarding their incarceration show similar trends experienced by the overall prison population.

Incarcerated women are also seeing their average minimum sentences increase, though women continue to receive generally shorter sentences than incarcerated people overall. In 2019, the average prison sentence for women was 7.3 years, up 2.8 percent from the average minimum sentence of 7.1 years in 2018. While it is an increase, the women’s 2019 average sentence is still 38.7 percent shorter than the overall average sentence.

Incarcerated women are also seeing their average minimum sentences increase, though women continue to receive generally shorter sentences than incarcerated people overall. In 2019, the average prison sentence for women was 7.3 years, up 2.8 percent from the average minimum sentence of 7.1 years in 2018. While it is an increase, the women’s 2019 average sentence is still 38.7 percent shorter than the overall average sentence.

But women have concerns in prison that men do not. Safe & Just Michigan recently hosted a conversation about instituting civic oversight for pregnant people in prison for the Day of Empathy. The talk included the topics of shackling during pregnancy and childbirth, issues surrounding breastfeeding and milk banking, and custody and visitation concerns. You can watch that conversation here.

These numbers provide an interesting glimpse into Michigan’s corrections system on the eve of the COVID-19 epidemic, but a year into the pandemic, we know much has already changed. Safe & Just Michigan will continue to monitor statistics published by the MDOC to glean useful information that should guide criminal justice reform policy, and we will share what we learn with you.

~ Barbara Wieland

Communications Specialist