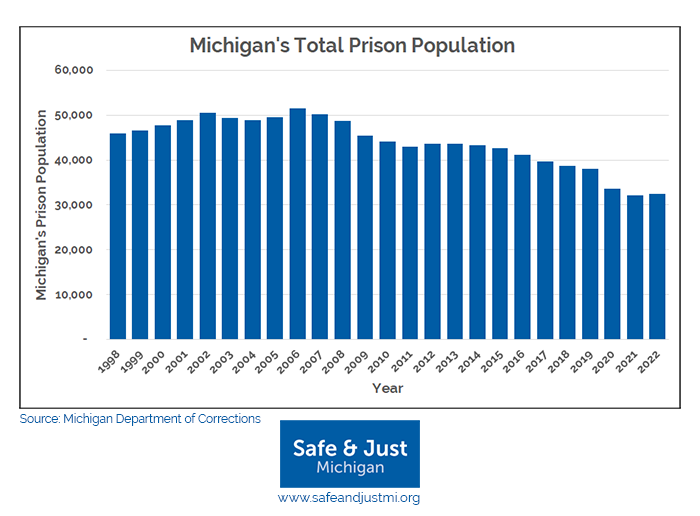

Michigan’s prison population nudged upward again for the first time in a decade, reversing a trend of rapidly falling headcounts inside prisons operated by the Michigan Department of Corrections. According to the figures recently published in the MDOC’s 2022 Statistical Report, there were 32,374 people incarcerated in Michigan prisons at the end of 2022, up 188 people or 0.6 percent from the year before.

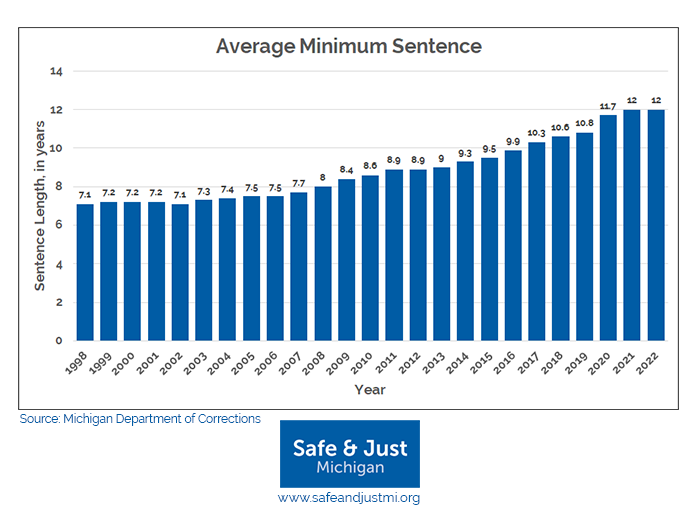

Meanwhile, the average minimum prison sentence in our state continues its upward climb. Michigan remains among the states with the longest prison sentences in the nation, and that doesn’t seem like it will change anytime soon.

While disappointing, the upward tick in the prison population wasn’t entirely surprising. The number of people incarcerated in Michigan had steeply fallen through the pandemic years. There were 38,053 people incarcerated at the end of 2019, at the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. That figure fell by 11.7 percent to 33,617 people in 2000 and another 4.2 percent to 32,186 people in 2021. While there was an effort in the early months of the pandemic to pull forward some people who would soon become eligible for parole, that wasn’t credited with the largest portion of the population drop. The sharp drop in the prison population during the pandemic was attributed, in larger part, to fewer prison intakes during the pandemic.

While disappointing, the upward tick in the prison population wasn’t entirely surprising. The number of people incarcerated in Michigan had steeply fallen through the pandemic years. There were 38,053 people incarcerated at the end of 2019, at the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. That figure fell by 11.7 percent to 33,617 people in 2000 and another 4.2 percent to 32,186 people in 2021. While there was an effort in the early months of the pandemic to pull forward some people who would soon become eligible for parole, that wasn’t credited with the largest portion of the population drop. The sharp drop in the prison population during the pandemic was attributed, in larger part, to fewer prison intakes during the pandemic.

As we reported at the time:

The largest factor that impacted the size of the prison population in 2020 was the sharply curtailed intake of new people into prison. A total of 3,866 people were added to the prison population in 2020 — 54.1 percent fewer than in 2019. This category includes newly sentenced people, people returning to prison after parole violations, people sent to prison after probation violations and one person who had previously escaped and received a new sentence.

Michigan also saw fewer returns to prison in 2020. These include categories such as technical parole violator returns, returns from court either with or without new sentences imposed, and returns from county jail. There were 2,173 people who returned to prison these ways in 2020, 59.8 percent fewer than the 3,635 people in 2019.

Now that pandemic-era safety measures have largely come to an end, those numbers are returning to normal well. In 2019, for instance, there were 8,167 prison commitments, including new court commitments, probation violations, parole violations and additional sentences imposed. A year later, with the pandemic in full swing, that number had fallen 44.3 percent to 4,551.

By 2022, the number of prison commitments was on the rise again. In 2022, there were 6,528 prison commitments — still down 20 percent from the pre-pandemic level seen in 2019, but up 27.5 percent from the 5,120 prison commitments seen in 2021.

Policies toward prison commitments and pull-forward parole dates may have fluctuated during the pandemic, but one thing that didn’t change was the steady uphill climb of Michigan’s average minimum prison sentence. Starting at 10.8 years in 2019, it rose to 11.7 years in 2019 and then 12 years in both 2021 and 2022.

Policies toward prison commitments and pull-forward parole dates may have fluctuated during the pandemic, but one thing that didn’t change was the steady uphill climb of Michigan’s average minimum prison sentence. Starting at 10.8 years in 2019, it rose to 11.7 years in 2019 and then 12 years in both 2021 and 2022.

This shouldn’t be entirely surprising, either. The COVID crisis spurred efforts to bring home as many people as possible in order to limit the spread of the disease and preserve lives. However, people who are serving long sentences with distant parole dates or life without parole sentences weren’t eligible to go home. That led to more people with shorter sentences being released, while those with longer sentences or life without parole sentences being left behind. At the same time, prisons were taking in fewer people — including fewer people with short sentences. As a result, the population left in prison tended to skew toward longer sentences.

While predictable, Michigan’s long prison sentences are a problem that can’t be ignored. We know that these long sentences do little to keep us safe, as people tend to age out of crime long before these sentences end. Meanwhile, Michigan taxpayers continue to pay upwards of $48,000 a year to keep someone incarcerated every year — more as a person gets older and their health care needs increase.

There are measures we could enact to change this. Bringing back Good Time or creating productivity credits would allow people to reduce long sentences in exchange for meeting conduct, educational or vocational training goals. Establishing a Second Look policy would give judges the opportunity to reconsider some of these long sentences and resentence someone, when appropriate. And establishing a sentencing commission could eliminate some of the long sentences we have on the books in the first place.

Safe & Just Michigan supports all the measures listed above and is working with our advocacy partners and supporters in the Legislature to make them a reality. We’ll keep you updated on the progress.

~Barbara Wieland

Senior Communications Specialist