Edward Sanders was just 17 years old in 1975 when a judge told him he would never walk free again. Though he hadn’t pulled the trigger, he had been convicted as an accessory to a first-degree homicide in Michigan, one of four states that still requires 17-year-olds to be tried as adults in certain cases. Edward’s life changed forever in that instant.

“It was devastating,” he said. “They allowed my father to come back to be with me for a bit, but it was devastating. It was the worst thing I experienced, and I relived that day over and over every day I was in prison.”

Despite what he heard from the judge, he never lost hope that he would one day be free.

“I had hope through a nourishing relationship with my creator,” Sanders said. “I looked for ways to serve others. Anytime I felt like there was no hope for me, I looked for ways to give hope to others.”

That, he said, sustained him.

Edward’s unshakable hope in the future led him to improve his education. He had been a remedial student when he entered prison, but during his incarceration, he completed his high school diploma and earned a bachelor’s degree in behavioral science from Spring Arbor University. He went on to study paralegal skills as well and put that knowledge to work serving others, filing legal papers and motions on their behalf. “I was a real jailhouse lawyer,” he said with a smile.

Still, Edward’s own freedom remained elusive for years. That started to change in 2012, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states couldn’t hand out life sentences to juveniles, calling that cruel and unusual punishment.

“When I heard about that ruling, my first thought was not about myself, but about the children still out there that this was going to save,” Sanders said. “Some say (the Supreme Court decision) is about a civil right, but to me, that’s more of a human right.”

Things didn’t change for Sanders immediately. The state of Michigan said that it would be impractical and too expensive to hold new hearings for the 350 people like Sanders who had been sentenced to life when they were juveniles and were still incarcerated.

But Michigan, along with other states that had resisted resentencing for juvenile lifers, was compelled to reverse course following a 2016 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said the 2012 ruling must be applied retroactively. That gave Sanders and people like him a chance at a real parole hearing.

Sanders’ opportunity came the following year. He finally got resentenced, which led him to being released on July 6, 2017. His parole ended the following May.

“I was 17 when I was sentenced, and when I came out, I was almost 60,” Sanders said.

Sanders is one of few juvenile lifers who’ve gotten a second chance from the state of Michigan so far. More than 200 are still incarcerated at the average cost of $35,000 per year, or more than $7 million annually. Safe & Just Michigan supports the work of partner organizations such as State Appellate Defender Office, the ACLU of Michigan that give more juvenile lifers a chance at a fair parole hearing.

Since re-entry, Sanders has held a job at McDonald’s and done work for an attorney’s office. His day-to-day challenges include finding reliable transportation, opening bank accounts and shopping for affordable health care. “It’s a blessing to have those problems,” Sanders said. “I keep it in perspective.”

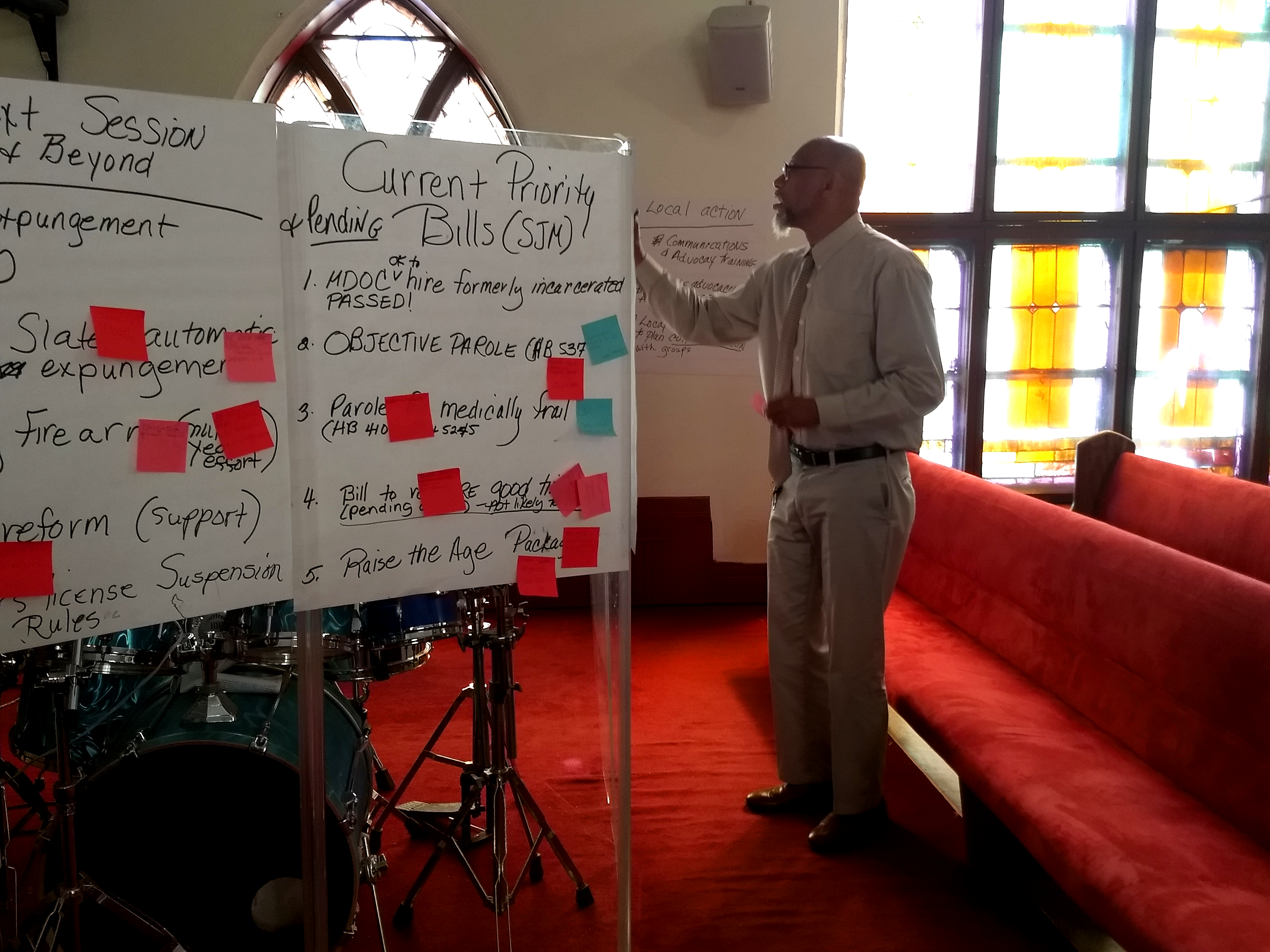

With four decades of experience in the criminal justice system, Sanders sees many ways it can be improved to become fairer and more effective. At Safe & Just Michigan’s recent Detroit Community Meeting, Sanders had the opportunity to outline his top three priorities in addressing the criminal justice system. His choices?

- Re-establishing a “Good Time” system to incentivize good behavior in prison

- Legislating objective parole to minimize the parole board’s subjective decision making

- Addressing long indeterminate sentencing in Michigan

“Good Time was the biggest corrections officer on the block,” Sanders said. “You’d have someone come in with a long sentence, but they knew if they behaved right, they could cut it down. Now that’s gone,” he said, referring to a Michigan ballot referendum that eliminated the “Good Time” system in 1978. “Now, there’s less reason to behave, and that makes it less safe for everyone. That needs to come back.”

The priorities Sanders outlined are ones we share. SJM is pursuing a policy agenda that will reduce over-reliance on incarceration and increase community safety and well-being.

SJM staff met Edward Sanders at its Detroit Community Meeting. He agreed to share his story.

First Year of Second Chance

An essay by Edward Sanders

Edward Sanders, July 14, 2018

July 6, 2018, marked a full year of re-entry back into society after having served 42½ years in Michigan prisons. I have accomplished many things in that time. I have many people to thank for assisting me in small and great ways.

Two groups in particular that I would like to give great thanks to are former and current members of the Detroit Lions and Pistons who gave warm and welcoming greetings to myself and other former juvenile lifers without parole at the Luck Inc. organization after we had been resentenced to term of years and released from Michigan state prisons. We had served various numbers of years from 25 up to 40 plus. More importantly, I would like to thank them for their appeal to our current attorney general and county prosecutors.

This stance of these courageous current and former NBA and NFL players is significant in that too often, voices of such members of society are silent because of their status — their careers, endorsements and public persona. These players not only met and spoke with myself and other former juvenile lifers without parole, but they listened to us, gave us advice and encouragement, and further took a very significant public stance.

On June 20, 2018, the Port Huron Times Herald reported the Michigan State Supreme Court held in People vs. Skinner that judges will be allowed to resentence juvenile defendants to life in prison. Before that, jury hearings were required for the resentencing of more than 218 remaining juvenile lifers in Michigan prisons.

To quote Angela LaChica, a writer for the online news site The Appeal: “(The state attorney general and county prosecutor) should let individuals convicted as children plead their cases to a parole board after spending decades in prison, exercising empathy instead of relying on overly harsh juvenile sentences. State legislators can also pass legislation to end juvenile life without parole.”

The above essay was written by Edward Sanders and reflects his opinions. It has been lightly edited by SJM staff with his approval.