While Michigan has seen its overall prison population steadily fall over the past years, this not been the case for incarcerated women.

It’s important to note that women still comprise a very small percentage of the state’s overall prison population — just 5.4 percent. Unlike the male population, which is spread out among nearly 30 prison facilities across the state, all the women are incarcerated in one location — the Huron Valley Women’s Correction Facility in Ypsilanti. The women who live there are different from their male counterparts in several ways: They typically have shorter prison stays than men, they are often there for different reasons, and they may face different challenges during their time in prison.

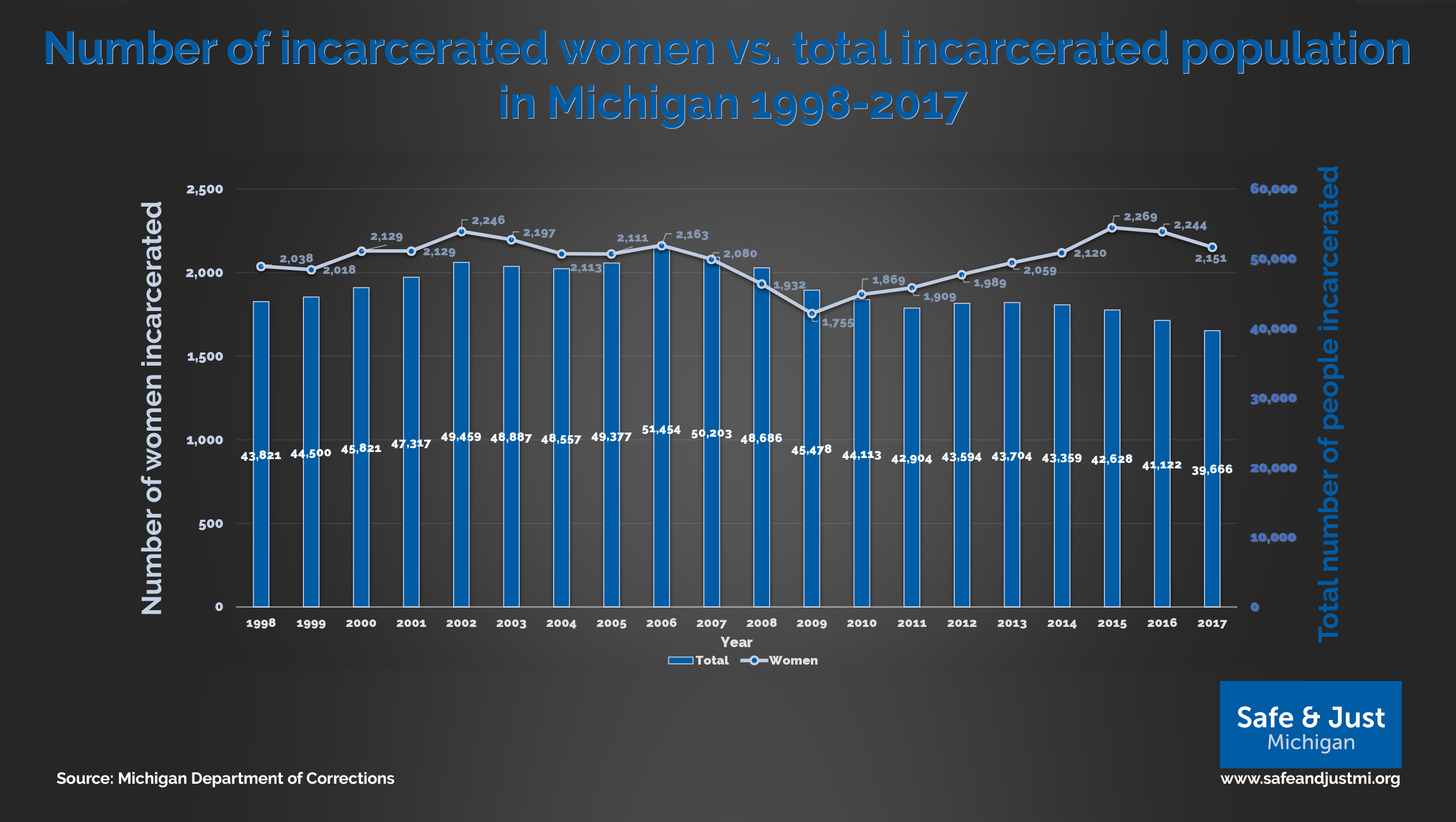

Ten years ago, there were 1,755 women incarcerated at the Huron Valley Women’s Correctional Facility. In 2017, the last year for which figures were available, that number had risen to 2,151, an increase of 22.6 percent. In the same time period, the overall state prison population has fallen 12.8 percent from 45,478 a decade ago to 39,666 in 2017.

At the same time, incarcerated women have seen an increase in the length of stay. The average minimum sentence served by women in Michigan has increased 15.5 percent from 5.8 years in 2007 to 6.7 years in 2017.

What’s happening in Michigan mirrors a national trend. A 2018 Prison Policy Institute report found that women’s incarceration nationwide has grown at twice the pace of men’s incarceration. Women still comprise a comparatively small percentage of the total number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons and county jails, but they are narrowing that gap at a quick pace.

However, when women are sentenced to prison in Michigan, it’s for notably shorter sentences than for men. The average minimum women’s prison sentence in our state was 6.7 years in 2017, compared to the overall sentence of 10.3 years overall. Even so, the average women’s prison sentence has been growing over the years, just as it has been for everyone. Since 1998, when the average minimum sentence was 4.8 years, the length of women’s average sentence has increased 39.5 percent. That’s slightly less than the overall average increase statewide of 45.1 percent from 1998, when the average sentence for both men and women was 7.1 years.

What’s driving the different sentence lengths? A part of that comes from the fact that men and women are often committed to prison for different reasons.

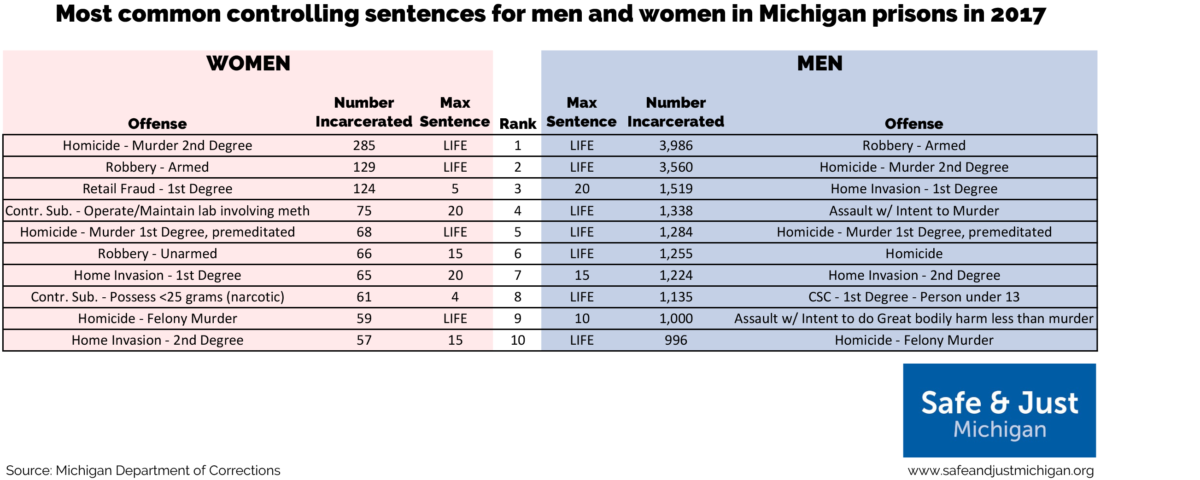

In 2017, both men and women shared the same top two controlling offenses. A controlling offense is the longest sentence an incarcerated person has to serve, so if a person receives a two-year sentence for writing a check on an account that doesn’t exist as well as a five-year identity theft sentence, the five-year sentence would be the controlling offense. In 2017, second-degree murder and armed robbery were the most common controlling offenses for both men and women.

From there, the similarities start to change — sometimes drastically.

Among the top-ten controlling offenses for men, seven of them carried possible life sentences. For women, only four did. Furthermore, two of the top-10 most common controlling offenses for women carried relatively short sentences — a possible four-year sentence for possessing less than 25 grams of a narcotic (eighth-most common controlling offense for women) and a possible five-year sentence for first-degree retail fraud (third-most common controlling offense for women). For men, none of the top-10 most common controlling offenses carried anything less than a possible 10-year sentence.

But it would be a mistake to assume that because women typically serve shorter sentences that they face fewer challenges in Michigan’s corrections system. Instead, many of the problems they face are unique.

For instance, the fact that all women are assigned to one facility presents its own challenges. The location of the facility — in the southeastern corner of the state — is doubtlessly more convenient for families who live in the metro Detroit area. But it makes visitation for families from Northern Michigan and the Upper Peninsula a considerable hardship. From a place like Hancock in the far corner of the Upper Peninsula, the women’s prison is about a nine-hour drive without stops. Unlike families with a male relative who is incarcerated, there is no hope that she will ever be moved to a closer facility during her time of confinement. And that matters, because studies have shown that people who are incarcerated stand a greater chance of successful reintegration after their release and therefore a lower risk of recidivism if they maintain family relationships during their time of incarceration.

There are also challenges faced by women in confinement that don’t arise among men, such as pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding and menstruation. And, while the Michigan Department of Corrections has updated its rules to say that only soft restraints should be used on pregnant women, including during delivery, there is movement among advocates to institute policies that do more to preserve the dignity of incarcerated women.

Nationwide, the rise in the women’s prison population and some of the unique challenges they face are starting to gain more attention. This has already resulted in a few changes, such as laws for federal prisons that make menstrual products free of charge and the shackling of pregnant women in most cases. Safe & Just Michigan will let you know if similar reforms gain traction at the state level.