(This is the second post in a series Safe & Just Michigan is running on Michigan’s habitual offender laws. Other posts include: Can my sentence be used against me and more to be written as the series continues.)

At Safe & Just Michigan, we generally use human-centered language. However, to keep technical concepts clear in this blog, we will adhere to legal terminology, which is unfortunately not human-centered.

As detailed in an earlier blog, significant changes have recently been proposed to Michigan’s habitual sentencing enhancement laws. To better understand why these changes are needed, we are examining the use of habitual sentencing enhancements in Michigan.

The application of habitual sentencing enhancements is a matter of discretion for prosecutors which varies greatly. The status can be applied to a person who has been convicted of a prior felony, even if the prior conviction is unrelated to the current offense or was long ago and can result in an increased sentence.

Eligibility and Application of Habitual Sentencing

According to a report by the former Criminal Justice Policy Commission, most felony convictions in Michigan are eligible to have a habitual sentencing enhancement added, but few are. Almost 60 percent of felony convictions between 2012 and 2017 in Michigan were eligible to have habitual sentencing enhancements. However, in 70 percent of these cases, the sentencing enhancement was not applied. Looking at the big picture, habitual sentencing enhancements are applied in only 17 percent of all felony convictions between 2012 and 2017. Although this is happening to a smaller portion of felony convictions, understanding what crimes are most often habitualized and to what degree is important.

According to a report by the former Criminal Justice Policy Commission, most felony convictions in Michigan are eligible to have a habitual sentencing enhancement added, but few are. Almost 60 percent of felony convictions between 2012 and 2017 in Michigan were eligible to have habitual sentencing enhancements. However, in 70 percent of these cases, the sentencing enhancement was not applied. Looking at the big picture, habitual sentencing enhancements are applied in only 17 percent of all felony convictions between 2012 and 2017. Although this is happening to a smaller portion of felony convictions, understanding what crimes are most often habitualized and to what degree is important.

Examining the eligibility in more depth, more than 174,000 convictions were eligible for habitual enhancement over six years. That creates an average of a little less than 30,000 felony convictions a year eligible for the habitual enhancement. Assessing the application further reveals that in those six years, almost 52,000 felony convictions had the status applied, which is an average of 8,632 habitual sentencing enhancements applied each year.

Degrees of separation

We can further see how prosecutors choose to apply the habitual enhancement when we consider the second-, third- and fourth habitual offender sentences. The level of habitual status eligible is dependent on the number of prior felony convictions. To be charged as a second habitual offender, a person would need to have 1 prior felony conviction, for a third, two priors, and for a fourth habitual offender three or more prior felony convictions.

The level applied is vital, as it directly relates to the increase in the sentence given for the offense. Under the Michigan Sentencing Guidelines convictions sentenced as second habitual offenders can have the maximum sentence increased by 25 percent, 50 percent for third, and 100 percent for fourth habitual offenders.

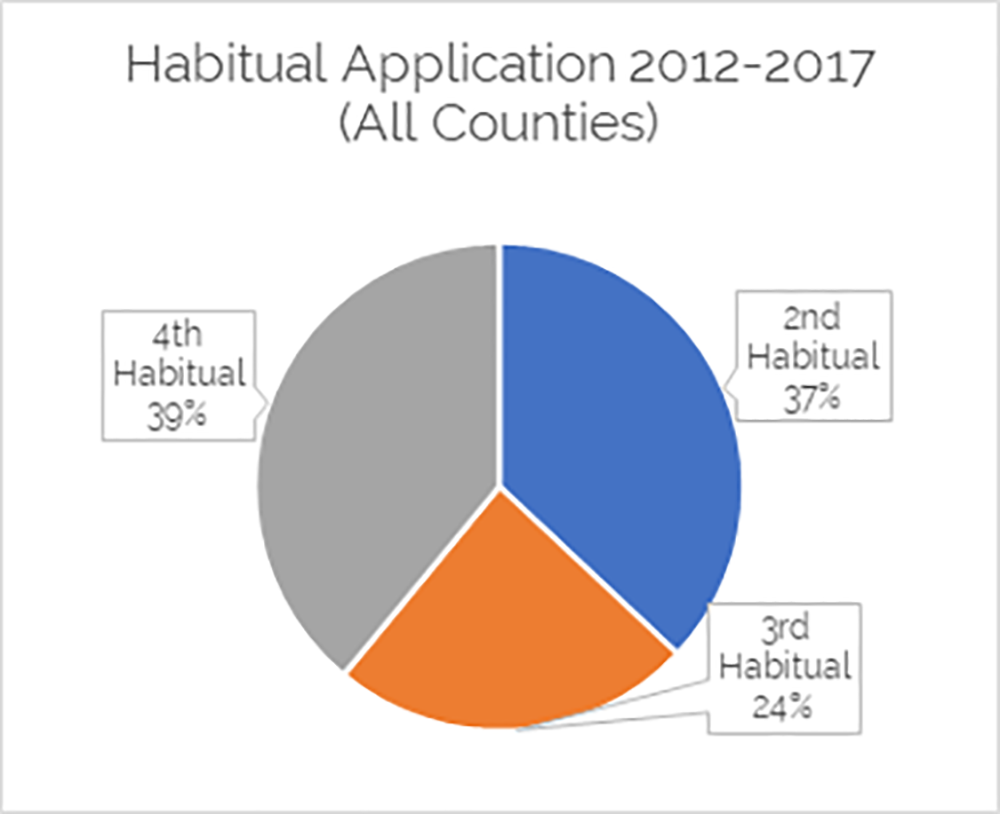

Numbers show that slightly more felony convictions are charged as fourth habitual offenders than second, and third habitual offender sentences are charged the least.

Of the habitual sentencing enhancements charged between 2012 and 2017 almost 40 percent were fourth habitual offender enhancements, allowing a doubling of the minimum sentence. Second habitual offenders follow closely behind at 37 percent, and third habitual offenders’ makeup less than one quarter than the habitual enhancement applications.

Application of Habitual Sentencing by Offense Characteristics: Crime Group

Under the Michigan Sentencing Guidelines, there are two major ways to categorize felony convictions: by crime group and crime class. All offenses included on the guidelines belong to one of the six crime groups, relating to the nature of the offense. The six groups are:

- Crimes against a person (person)

- Crimes against property (property)

- Crimes involving controlled substances (CS)

- Crimes against public order (public order)

- Crimes against public safety (public safety), and

- Crimes against the public trust (public trust).

It is important to note that within the crime group, the severity of offense varies greatly. That is related to the crime class and will be discussed in our next blog post in this series.

— Crimes against a person include offenses such as murder, first-degree sexual assault and armed robbery. Also included are offenses that might not be as intuitive — such as cyberbullying — that result in serious injury, resisting an officer or using the internet for certain crimes.

— Crimes against property include many offenses, such as fraud, larceny and some degrees of arson.

— Crimes involving controlled substances include offenses related to the possession, manufacturing and delivery of illegal substances.

— Crimes against public order include a wide range of offenses such as gambling offenses, money laundering and identity theft.

— Crimes against public safety include offenses related to operating machinery while intoxicated, adulterated and misbranded drugs and food, and impersonating a peace officer.

— Crimes against public trust include offenses of perjury, election tampering and failure to file tax returns.

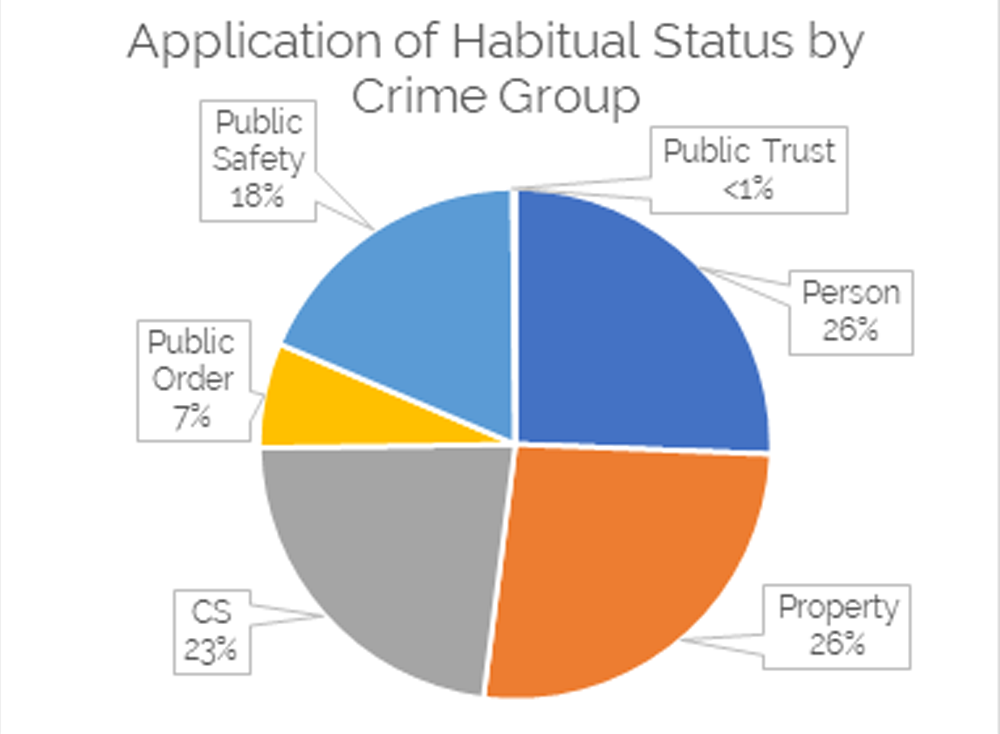

The first pie chart above shows the percent eligible to have the habitual sentencing enhance by crime group. The second pie chart to the right shows the application of the habitual sentencing enhancement and are very similar.

The first pie chart above shows the percent eligible to have the habitual sentencing enhance by crime group. The second pie chart to the right shows the application of the habitual sentencing enhancement and are very similar.

However, one notable difference can be seen in the group of crimes against public trust, There, 3 percent of the offenses were eligible for habitual status, but less than 1 percent saw them applied. In fact, of the over 5,000 eligible cases, only 82 were habitualized. Despite a few small differences the eligibility and application of habitual status are very similar.

Safe & Just is dedicated to understanding how sentencing enhancements are used in Michigan and their reform.

~Anne Mahar

Research Specialist